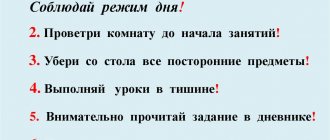

Approaches to understanding the term “consciousness”

At various times, consciousness has acted as a type of mental state or as a way of perceiving and relating to others. It is often described as a point of view, as "I". Many researchers consider this category as the most important thing in the world. On the other hand, many of them tend to define the concept of “consciousness” too vaguely.

Definition 2

Consciousness is a state of mental life of an individual, which is expressed through the subjective experience of events in the external world and the life of the person himself. It is a form in which objective reality is reflected with the help of the human psyche.

Are you an expert in this subject area? We invite you to become the author of the Directory Working Conditions

In accordance with the cultural-historical approach, a characteristic feature of consciousness is represented by the fact that the intermediate link between objective reality and consciousness includes elements of social and historical practice. All this makes it possible to build objective (generally accepted) pictures of the world.

In Russian psychology, a generally accepted understanding of consciousness has been formed as the highest form of the psyche, emerging in human society with the advent of collective work, communication, language and speech. This principle was set out in their works by S. L. Rubinshtein, E. V. Shorokhov, A. N. Leontyev.

Consciousness and self-observation data

As a constitutive fact of internal life, S. is potentially open to introspection, which allows us to highlight several in it. characteristic phenomena: 1) many specific ones. sensory qualities, or “qualia” (Latin qualia – properties), constituting the “sensory fabric” of the image (A. N. Leontyev); 2) decomp. the degree of clarity of the contents of the S., some of which are, as it were, in the “focus” of the S., while others form its blurred periphery (in the case of emotional experiences, such a periphery, or background, is the person’s mood); 3) a sense of freedom of choice and the ability to arbitrarily determine the nature of at least the simplest actions performed (see Free will).

The last group of phenomena indicates the presence in episodes of self-awareness of a person playing the role of observer, arbiter and initiator of decisions made (see Personality). It is no coincidence that the expressions “come to consciousness” and “come to your senses” are almost synonymous. Internal “theater for oneself” (N.N. Evreinov) often includes several characters, which characterizes S.’s dialogical nature: we notice that we are carrying on internally with ourselves or with someone else. dialogue, we look at ourselves from the outside through the eyes of those around us, we evaluate others depending on how they evaluate us, we try to imagine how we would act in the place of another or how another person would behave in our situation.

Consciousness in psychology

The essence of consciousness is usually defined through a person’s ability to abstract (verbal) thinking. Its tool and means is language, which arose in human society. Through language, knowledge of the laws of nature and society occurs.

Note 1

L. S. Vygotsky wrote that consciousness is a reflection of reality by the subject, his determination of his activities and himself. Consciously, according to the researcher, that which can be transmitted as a stimulus to other reflex systems (that which is capable of causing a response in them).

Finished works on a similar topic

Course work Consciousness as a subject of psychology 480 ₽ Abstract Consciousness as a subject of psychology 280 ₽ Test work Consciousness as a subject of psychology 200 ₽

Receive completed work or specialist advice on your educational project Find out the cost

Individual consciousness exists only in the presence of social consciousness and language, which is its real substrate. Consciousness did not exist initially, it is not generated by nature, but arises due to the existence of society. For this reason, consciousness is not always a postulate or a condition of psychology, but represents its problem (the subject of specific scientific and psychological research).

Vygotsky's elements of consciousness include verbal meanings as a system that operates as a whole. This working system represents the state of wakefulness, the specific human characteristic of being awake.

From the position of B. G. Ananyev, consciousness can act as an element of the effect of action. The initial facts of consciousness are the following components:

- Perception,

- An individual's experience of the results of his own actions.

Gradually, not only the effects of actions, but also the processes of activity themselves become amenable to awareness. Individual development of consciousness occurs through the transition from consciousness of the corresponding moments of action to purposeful and planned activity. The state of wakefulness is considered to be a continuous “flow” that switches from one type of activity to another.

Properties of consciousness.

S. L. Rubinstein identifies the following properties of consciousness:

Psychology bookap

* building relationships;

* cognition;

* experience.

Psychology bookap

Each act of consciousness can rarely be either only cognition, or only experience, or only attitude; more often it includes these three components. However, the degree of expression of each of these components is very different. Therefore, each act of consciousness can be considered as a point in the coordinate system of these three most important psychological categories. See: Rubinstein S. L. Being and consciousness. - M., 1957.

When analyzing the mechanisms of consciousness, it is important to overcome the so-called brain metaphor. Consciousness is a product and result of the activity of systems, which include both the individual and society, and not just the brain. The most important property of such systems is the possibility of creating the functional organs they lack, a kind of new formations that, in principle, cannot be reduced to certain components of the original system. Consciousness must act as a “superposition of functional organs.”

Properties of consciousness as a functional organ:

* reactivity;

Psychology bookap

* sensitivity;

* dialogism;

* polyphony;

Psychology bookap

* spontaneity of development;

* reflexivity.

Functions of consciousness.

The main functions of consciousness include the following:

Psychology bookap

* reflective;

* generative (creative, or creative);

* regulatory and evaluation;

Psychology bookap

* reflective;

* spiritual;

Literature.

1. Platonov K.K. About the system of psychology. - M.: Mysl, 1972.

2. Rubinstein S. L. Being and consciousness. - M., 1957.

Can radical ideas explain consciousness?

Today, scientists cannot come close to studying consciousness. The situation is limited by the fact that on the one hand, neuroscientists study areas of the brain that are associated with conscious activity - for example, recognizing faces, the sensation of pain or states of happiness. But the science of consciousness is still a science of relationships; it does not explain anything. We know that certain areas of the brain are responsible for certain types of conscious responses, but we don't know why. In recent years, a huge number of discoveries have been made about the functioning of various areas of the brain. So, just recently we told you that scientists managed to discover a completely new signal in the human brain, which no one knew about before. This is great, but does it bring us any closer to answering the question of what consciousness is?

According to the theory of panpsychism, the Universe is conscious (but this is not certain)

In a Ted Talk, Australian psychologist specializing in the philosophy of mind, David Chalmers, compares the human mind to a subjective movie that constantly plays before our eyes. The question that worries scientists most is why behavior—which can be explained in biological terms, as Stanford neurobiology professor Robert Sapolsky brilliantly does—is accompanied by subjective experience. But we cannot explain the presence of this subjective experience in the same way that physics explains chemistry, chemistry explains biology, and biology, partially, explains psychology. In order to understand what consciousness is, radical ideas are needed.

This is exactly what Daniel Dennett proposes. In his opinion, there are no difficult problems in the study of consciousness. According to Dennett, the whole idea of this subjective cinema implies an illusion that the brain gives us. Therefore, science can only explain the objective functioning of brain behavior. Dennett's idea, in my opinion, is the most realistic of all others. But to create such a neurobiological theory of consciousness, a large amount of research is needed.

This is interesting: Will robots be able to gain consciousness?

Those who disagree that consciousness is just an illusion skillfully created by the brain propose even more radical theories of consciousness. Thus, David Chalmers proposes to consider consciousness as something fundamental - like the fundamental laws of physics. In physics, the fundamental concepts are space, time, and mass. Based on these concepts, scientists derive further principles and laws - the law of universal gravitation, the laws of quantum mechanics, etc. It is noteworthy that all of the listed fundamental properties and laws are no longer explained in any way. We accept them as elementary and build a picture of the world on their basis. Such an approach, according to Chalmers, opens up new opportunities for science, since it will require the study of the fundamental laws that govern consciousness. These laws must also connect consciousness with other fundamental principles - space, mass, time and other physical processes. We don't know what these laws are, but we can try to find them.

Modern physics considers a Universe in which the fundamental forces of nature operate

The second no less radical and, perhaps, crazy idea that Chalmers talks about is panpsychism. The theory that consciousness is universal and every system has it to some extent. According to this theory, or better yet, hypothesis, even elementary particles and photons have consciousness. The idea itself, of course, is not that electrons and photons are intellectually developed, but that these particles have some kind of primitive sense of consciousness. Although this idea seems counterintuitive to us, to people from cultures that view the human mind as one with nature, the theory of panpsychism seems quite logical.

Which of the above ideas seems most plausible to you? Share your opinion in the comments and with participants in our Telegram chat.

And yet, to find the answer to the question of what consciousness is, it is worth paying attention to how the brain evolved. After all, we send rockets into space and have defeated dangerous diseases like smallpox thanks to science. This means that sooner or later, scientists will be able to create a unified theory of consciousness.

Yu.B. Gippenreiter. Psychology as a science of consciousness Added by Psychology OnLine.Net 09/25/2005 (Edit 04/03/2008) We are moving to a new major stage in the development of psychology. Its beginning dates back to the last quarter of the 19th century, when scientific psychology took shape. The origins of this new psychology are the French philosopher Rene Descartes.

(1596-1650).

The Latin version of his name is Renatus Cartesius, hence the terms: “Cartesian philosophy”, “Cartesian intuition”, etc. Descartes graduated from the Jesuit school, where he showed brilliant abilities. He was especially interested in mathematics. She attracted him because she rested on clear foundations and was strict in her conclusions. He decided that the mathematical way of thinking should be the basis of any science. By the way, Descartes made outstanding contributions to mathematics. He introduced algebraic notation, negative numbers, and invented analytical geometry. Descartes is considered the founder of rationalist philosophy. According to his opinion, knowledge should be built on directly obvious data, on direct intuition. From it it must be deduced by logical reasoning. In one of his works, R. Descartes discusses how best to get to the truth [31]. He believes that a person from childhood absorbs many misconceptions, taking various statements and ideas on faith. So if you want to find the truth, then first you need to question everything. Then a person can easily doubt the testimony of his senses, the correctness of logical reasoning and even mathematical proof, because if God made a person imperfect, then his reasoning may contain errors. So, having questioned everything, we can come to the conclusion that there is no earth, no sky, no God, no our own body. But something will definitely remain. What will remain? Our doubt

- a sure sign that we are

thinking

.

And then we can claim that we exist, because “... when thinking, it is absurd to assume that something that thinks does not exist.” And then follows the famous Cartesian phrase: “I think, therefore I exist” (“cogito ergo sum”) [31, p. 428]. “What is thought?” - Descartes asks himself further. And he answers that by thinking he means “everything that happens in us,” everything that we “perceive directly by ourselves.” And therefore, to think means not only to understand

, but also to “

desire

”, “

imagine

”, “

feel

” [31, p.

429]. These statements of Descartes contain the basic postulate from which the psychology of the late 19th century began to proceed - a postulate that states that the first thing a person discovers in himself is his own consciousness

.

The existence of consciousness is the main and unconditional fact, and the main task

of psychology is to analyze the state and content of consciousness.

Thus, the “new psychology”, having adopted the spirit of Descartes’ ideas, made consciousness

.

What do they mean when they talk about states and contents of consciousness? Although they are assumed to be directly known to each of us, let us take as an example a few specific descriptions taken from psychological and literary texts. Here is one excerpt from the book of the famous German psychologist W. Köhler “Gestalt Psychology”, in which he tries to illustrate those contents of consciousness that, in his opinion, psychology should deal with. In general, they form a certain “picture of the world.” “In my case <...> this picture is a blue lake surrounded by a dark forest, a gray cold rock against which I leaned, the paper on which I write, the muted noise of leaves barely swayed by the wind, and this strong smell coming from the boats and catch. But the world contains much more than this picture. I don’t know why, but suddenly a completely different blue lake, which I admired several years ago, flashed in front of me. Illinois. For a long time, it has become common for me to have such memories appear when I am alone. And this world contains many other things, for example, my hand and my fingers, which fit on paper. Now that I have stopped writing and look around me again, I feel a sense of strength and well-being. But a moment later I feel a strange tension in myself, turning almost into a feeling of being trapped: I promised to deliver this manuscript finished in a few months.” In this passage we are introduced to the content of consciousness, which W. Köhler once found in himself and described. We see that this description includes images of the immediate surrounding world, and memory images, and fleeting feelings about oneself, one’s strength and well-being, and an acute negative emotional experience. I will give another excerpt, this time taken from the text of the famous natural scientist G. Helmholtz

, in which he describes the thinking process.

“...A thought dawns on us suddenly, without effort, like inspiration <...> Each time I first had to turn my problem around in every possible way, so that all its bends and plexuses lay firmly in my head and could be learned again by heart, without the help of writing.</…>

It is usually impossible to get to this point without a lot of continuous work.

Then, when the fatigue passed, an hour of complete bodily freshness and a feeling of calm well-being was required - and only then did good ideas come” [26, p. 367]. Of course, there is no shortage of descriptions of “states of consciousness,” especially emotional states, in fiction. Here is an excerpt from the novel “Anna Karenina” by L.N. Tolstoy, which describes the experiences of Anna’s son, Seryozha: [quote] “He did not believe in death in general, and especially in her death... and therefore and after he was told that she died, he looked for her during the walk. Every woman, plump, graceful, with dark hair, was his mother. At the sight of such a woman, a feeling of tenderness rose in his soul, such that he gasped and tears came to his eyes. And he was just waiting for her to come up to him and lift her veil. Her whole face will be visible, she will smile, hug him, he will hear her smell, feel the tenderness of her hand and cry happily... Today, stronger than ever, Seryozha felt a surge of love for her and now, having forgotten himself <...> he cut up the entire edge of the table with a knife, looking ahead with shining eyes and thinking about her” [112, vol. IX, p. 102].[quote] It is unnecessary to remind that all the world’s lyrics are filled with descriptions of emotional states, the subtlest “movements of the soul.” Here is at least this excerpt from the famous poem by A.S. Pushkin: And the heart beats in ecstasy, And for it, And deity, and inspiration, And life, and tears, and love have risen again. Or from the poem by M. Yu. Lermontov: A burden falls from the soul, Doubt is far away - And one believes and cries, And so easily, easily... So, this is the complex reality that psychologists ventured to study at the end of the last century. How to conduct such a study? First of all, they believed, it is necessary to describe the properties of consciousness

.

The first thing we discover when looking at the “field of consciousness” is the extraordinary diversity of its contents, which we have already noted. One psychologist compared the picture of consciousness to a flowering meadow: visual images, auditory impressions, emotional states and thoughts, memories, desires - all this can be there at the same time. However, this is not all that can be said about consciousness. Its field is heterogeneous in another sense: a central region clearly stands out in it, especially clear and distinct; this is the “ field of attention

”, or the “

focus of consciousness

”;

outside it there is a region whose contents are indistinct, vague, undifferentiated; this is the “ periphery of consciousness

.”

Further, the contents of consciousness that fill both described areas are in continuous movement. V. James

, who wrote a vivid description of various phenomena of consciousness, distinguishes two types of its state: stable and changeable, quickly passing.

When we, for example, think, our thoughts dwell on the images in which the subject of our reflection is clothed. Along with this, there are subtle transitions from one thought to another. The whole process is generally similar to the flight of a bird: periods of calm soaring (stable states) are interspersed with flapping wings (variable states). Transitional moments from one state to another are very difficult to catch by self-observation, because if we try to stop them, then the movement itself disappears, and if we try to remember them after they are over, then the bright sensory image that accompanies stable states overshadows the moments of movement. V. James reflected the movement of consciousness, the continuous change of its contents and states in the concept of “ stream of consciousness

”.

The flow of consciousness cannot be stopped; not a single past state of consciousness is repeated. Only the object of attention can be identical, and not the impression of it. By the way, attention is maintained on an object only if more and more new aspects are revealed in it. Further, it can be found that the processes of consciousness are divided into two large classes. Some of them occur as if by themselves, others are organized and directed by the subject. The first processes are called involuntary

, the second -

voluntary

.

Both types of processes, as well as a number of other remarkable properties of consciousness, are well demonstrated using the device that W. Wundt used in his experiments. This is a metronome; its direct purpose is to set the rhythm when playing musical instruments. In W. Wundt's laboratory, it became practically the first psychological device. V. Wundt suggests listening to a series of monotonous clicks of the metronome. You can notice that the sound series in our perception involuntarily becomes rhythmic. For example, we can hear it as a series of paired clicks with an accent on every second sound (“tick-tock”, “tick-tock”...). The second click sounds so much louder and clearer that we can attribute this to an objective property of the metronome. However, such an assumption is easily refuted by the fact that, as it turns out, it is possible to arbitrarily change the rhythmic organization of sounds. For example, start hearing an accent on the first sound of each pair (“tak-tick”, “tak-tick”...) or even organize sounds into a more complex four-click beat. rhythmic

in nature , concludes V. Wundt, and the organization of rhythm can be either voluntary or involuntary [20, p.

10]. With the help of a metronome, W. Wundt studied another very important characteristic of consciousness - its “ volume

”.

He asked himself the question: how many separate impressions can consciousness accommodate at the same time? Wundt's experiment consisted of presenting a series of sounds to the subject, then interrupting him and giving a second series of the same sounds. The subject was asked: were the rows the same length or different? At the same time, it was forbidden to count sounds; you just had to listen to them and form a holistic impression of each row. It turned out that if the sounds were organized into simple measures of two (with emphasis on the first or second sound of the pair), then the subject was able to compare rows consisting of 8 pairs. If the number of pairs exceeded this figure, then the rows disintegrated, that is, they could no longer be perceived as a whole. Wundt concludes that a series of eight double beats (or 16 separate sounds) is a measure of the volume of consciousness

.

Then he puts on the following interesting and important experiment. He again asks the subject to listen to the sounds, but randomly organizes them into complex bars of eight sounds each. And then repeats the procedure for measuring the volume of consciousness. It turns out that this time the subject can hear five such measures of 8 sounds as a complete series, i.e. 40 sounds in total! With these experiments, W. Wundt discovered a very important fact, namely, that human consciousness is capable of being almost infinitely saturated with some content if it is actively united into larger and larger units. At the same time, he emphasized that the ability to enlarge units is found not only in the simplest perceptual processes, but also in thinking. Understanding that a phrase consisting of many words and an even larger number of individual sounds is nothing more than an organization of a higher-order unit. Wundt called the processes of such organization “ acts of apperception

.”

So, a lot of painstaking work has been done in psychology to describe the overall picture

and

properties

of consciousness: the diversity of its contents, dynamics, rhythm, heterogeneity of its zero, volume measurement, etc. Questions arose: how to explore it further?

What are the next tasks of psychology? And here a turn was made that eventually led the psychology of consciousness to a dead end. Psychologists decided that they should follow the example of the natural sciences, such as physics or chemistry. The first task of science, scientists of that time believed, was to find the simplest elements

.

This means that psychology must find the elements of consciousness, decompose the complex dynamic picture of consciousness into simple, then indivisible, parts. This is the first thing. The second task is to find the laws of connection of the simplest elements. So, first decompose consciousness into its component parts, and then reassemble it from these parts. This is how psychologists began to act. W. Wundt declared individual impressions, or sensations

.

For example, in experiments with a metronome these were individual sounds. But he called pairs of sounds, i.e. those very units that were formed due to the subjective organization of a series, complex elements, or perceptions. Each sensation, according to Wundt, has a number of properties or attributes. It is characterized primarily by quality (sensations can be visual, auditory, olfactory, etc.), intensity, extent (i.e. duration) and, finally, spatial extent (the last property is not inherent in all sensations, for example, it is present in visual sensations and absent from auditory ones). Sensations with their described properties are objective elements

of consciousness.

But they and their combinations do not exhaust the contents of consciousness. There are also subjective elements

, or feelings. V. Wundt proposed three pairs of subjective elements - elementary feelings: pleasure-displeasure, excitement-calm, tension-release. These pairs are independent axes of three-dimensional space of the entire emotional sphere. He again demonstrates the subjective elements he has highlighted on his favorite metronome. Suppose the subject organized sounds into certain beats. As the sound series is repeated, he constantly finds confirmation of this organization and each time experiences a feeling of pleasure. Now, suppose the experimenter greatly slowed down the rhythm of the metronome. The subject hears a sound and waits for the next one; he feels a growing sense of tension. Finally, the click of the metronome comes - and there is a feeling of release. The experimenter increases the clicks of the metronome - and the subject has some additional internal sensation: this is excitement, which is associated with the accelerated rate of clicks. If the pace slows down, then calmness occurs. Just as the pictures of the external world that we perceive consist of complex combinations of objective elements, i.e., sensations, our internal experiences consist of complex combinations of the listed subjective elements, i.e., elementary feelings. For example, joy is pleasure and excitement; hope - pleasure and tension; fear is displeasure and tension. So, any emotional state can be “decomposed” along the described axes or assembled from three simple elements. I will not continue the constructions that the psychology of consciousness dealt with. We can say that she did not achieve success on this path: she was not able to assemble living, full-blooded states of consciousness from simple elements. By the end of the first quarter of our century, this psychology practically ceased to exist. There were at least three reasons for this: 1) it was limited to such a narrow range of phenomena as the content and state of consciousness; 2) the idea of decomposing the psyche into its simplest elements was false; 3) the method that the psychology of consciousness considered the only possible - the method of introspection - was very limited in its capabilities. However, the following should be noted: the psychology of that period described many important properties and phenomena of consciousness and thereby posed many problems that have been discussed to this day. We will consider in detail one of these problems raised by the psychology of consciousness in connection with the question of its method in the next lecture.

| Description | Classical ideas about consciousness. The problem of consciousness in the philosophy of modern times. Facts of consciousness. Properties of consciousness. Elements of consciousness. |

| Rating |

0/5 based on 0 votes. Median rating 0. |

| Tags | consciousness, subject of psychology, hippenreiter |

| Views | . On average per day. |

| Related articles | E. Titchener. Postulates of structural psychology |

| Similar articles | Yu.B. Gippenreiter. Psychology as the science of behavior John Brodes Watson. Psychology as a science of behavior: Systematic personality change Yu. B. Gippenreiter, V. Ya. Romanov. Psychology of constitutional differences by W. Sheldon A. Adler. Science of living Michael Cole. Culture and cognitive science |