Worldview, worldview and worldview

worldview, worldview and worldview in different ways .

Attitude is the emotional and psychological side of the worldview. It expresses the sensations, perceptions, and experiences of people.

In a worldview based on visual representations, the world appears in its reality, the images of which are mediated by a combination of emotional, psychological and cognitive experience of people.

Worldview is formed on the basis of attitude and worldview. As science develops, the nature of the worldview is increasingly influenced by the knowledge it acquires. The importance of worldview lies in the fact that it is the basis for the formation of a person’s needs and interests, his ideas about norms and values, and therefore his motives for activity. The development and improvement of worldview, worldview and understanding of the world leads to an increase in the quality of the content of the worldview and an increase in the power of its influence on living life.

As a system of beliefs, people’s worldview is formed on the basis of a wide variety of knowledge, but its final form is given by philosophy, which, as noted earlier, generalizes the attitudes contained in it and develops extremely general principles of both knowledge, understanding, and transformation of the world. The foundation of a worldview is information about normative formations that mediate its orientation and give it effectiveness. Philosophy is a means of forming and justifying the content of the most general, fundamental and therefore essential normative formations of the worldview that mediate the entire life support system of people. In this sense, it is justified to consider it as the basis of a worldview that a person uses in his interactions with the world and to endow it with a worldview function .

Epistemological function

Associated with this function is epistemological or theoretical-cognitive . The essence of this function lies in the ability of philosophy to carry out a theoretical study of human cognitive activity in order to identify mechanisms, techniques and methods of cognition. In other words, the theory of knowledge, by developing the principles and norms of knowledge, provides a person with the means by which people have the opportunity to comprehend the world, that is, to obtain true knowledge about it and thereby have a correct worldview that meets the requirements of modern times, on the basis of which effective practice.

Methodological function

Philosophy, being a means of developing the principles of human relations to the world and the custodian of knowledge about these principles, is able to act as a methodology, that is, as a doctrine of methods of cognition and transformation of reality. This means that philosophy has a methodological function . The term “methodology” is used in scientific literature in two senses: firstly, the word “methodology” denotes the doctrine of norms and rules of human activity; secondly, methodology is understood as a set of certain norms that mediate cognitive and practical actions with the aim of optimizing them. It can be argued that methodology as a set of principles and norms of activity acts as a manifestation of a worldview in action. The fulfillment of a methodological function by philosophy depends on the quality of the general principles of cognitive and practical activity of people developed within its framework, as well as on the depth of assimilation of knowledge of these principles by the people applying them.

Information and communication function

The nature of the assimilation of philosophical knowledge depends on the ability of philosophy as a system of knowledge to be transmitted from one person to another and to inform the latter about its content. This reveals the information and communication function of philosophy.

Value-orienting function

Philosophy as a body of knowledge about the most general principles of a person’s relationship to the world is at the same time a system of criteria for evaluative activity , in the role of which these principles act. Evaluative activity, possible on the basis of people's awareness of the criteria proposed by philosophy for the optimality and usefulness of a particular set of phenomena and actions, acts as a means of orienting these people in the world. Philosophy as a means of developing knowledge about values and a carrier of this knowledge, from the point of view of axiology, or the theory of values, is capable of performing a value-orienting function.

Critical function

This direction of realizing one of the purposes of philosophy is associated with the manifestation of its other purpose, expressed in the fulfillment of a critical function. Within the framework of philosophy, an assessment of what is happening in the world is carried out on the basis of the general ideas contained in philosophy about the norm and pathology of the phenomena and processes of reality surrounding a person. Philosophy's critical attitude to what is negatively assessed in spiritual and material life contributes to the development of measures aimed at overcoming what does not suit a person, seems pathological to him and therefore worthy of transformation. The critical function of philosophy can manifest itself not only in people’s relationships to the world, but also be realized in the course of self-assessment by specialists of its own content. Thus, the critical function of philosophy can be realized both in terms of stimulating the development of knowledge about the world and updating the world as a whole, and in terms of improving the content of philosophy itself.

Integrating function

As is known, philosophy generalizes the knowledge accumulated by humanity, systematizes and integrates it into a single system , and develops criteria for its subordination. This allows us to talk about the integrative function of philosophy in relation to knowledge.

In addition, philosophy formulates extremely general principles of the world order, as well as requirements for a person’s relationship to the world, society and himself. Having been learned during education and becoming the property of different people, such principles ensure that they form positions that are similar in content, which contributes to the integration of the social community into a single whole. This reveals another plan for the implementation of the integrating function of philosophy.

Ideological function

In close connection with these functions, philosophy is capable of recording and promoting the interests of social strata and groups of society , that is, acting as an ideology, performing an ideological function. This function may have specificity depending on the interests of which social groups this philosophy expresses. As we know, group interests can be progressive or reactionary. Depending on this, the direction of the implementation of the ideological function is determined, which can have a great influence on the manifestation of other functions of philosophy. Reactionary ideologies are able to slow down the development of philosophy, deform and distort its content, reduce its social value, and reduce the scope of its application in practice.

Educational function

An important role is played by the educational function of philosophy, which stems from the ability of this discipline to have, as knowledge about it is acquired, a formative effect on a person’s intellect. A person’s mastery of knowledge of philosophy, the formation of beliefs and activity skills that correspond to it are able to encourage a person to be active, creative and effective for people. If a person masters a reactionary philosophy, this can give rise to a passive attitude towards affairs, alienation from people, from the achievements of culture, or turn into activity directed against society or part of it.

Prognostic function

Along with the above functions, philosophy is engaged in forecasting and performs a prognostic function. Many philosophers of the past acted as prophets, predicting the future. Some of the forecasts were utopian, far from reality, but sometimes the prophecies of individual outstanding thinkers achieved great adequacy. Of course, it is difficult to foresee the future, but the value of philosophers’ warnings about looming dangers, for example, those generated by thoughtless and predatory consumption of natural resources, within the framework of the rules that the world economy uses today, is extremely high. For this poses the task of improving the norms regulating the connections between society and nature in order to ensure the survival of people.

Design function

Another function of philosophy is connected with the considered functions of philosophy—design. Due to the fact that philosophy reveals the mechanisms and most general trends in the development of nature, society and thinking, reveals the requirements, the observance of which ensures the operation of these mechanisms and trends, it is able to become the basis for influencing natural and social processes . Such influence must be organized to ensure its clear focus and obtain certain results. Preliminary design of the social environment, for example, in the conditions of territory development, urban planning, construction of plants and factories, requires the participation of philosophy, which, together with other sciences, is designed to develop the most general principles and norms that make up the normative framework for the creation and functioning of objects used to organize the life of people in an urbanized environment. and other environment. Philosophy is called upon to play the same role in the organization of economic space. In a narrower sense, the design function of philosophy is realized in the formation of patterns of cognitive and practical activity. Consideration of the functions of philosophy is an illustration of its large-scale role in social life, in organizing people’s activities aimed at understanding and transforming the world.

In the activities of an economist, the functions of the acquired philosophy are realized not only in the content of his professional practical and theoretical activities. The embodiment of ideological, epistemological, methodological and other functions of philosophy is carried out both in terms of awareness of macroeconomic problems and in their implementation at the level of microeconomic relations. At the same time, it becomes possible to generate innovative ideas, make informed decisions on their implementation, successfully implement them in economic activity, and flawlessly follow the requirements of economic relations accepted for execution and existing in society. In other words, philosophy, having become the property of an economist as a component of his professional training, can act as the foundation of his practical activity. The success of this activity will depend, among other things, on what philosophy the economist has mastered and how skillfully he can apply it in practice.

3 Philosophy of India and China

Confucianism is an amazing synthesis of philosophy, ethics and religion.

Confucius (in literature often referred to as Kun Fu-tzu - “teacher Kun” 551-479 BC) is an ancient Chinese philosopher, founder of Confucianism, the greatest teacher of his time.[3]

The time when this thinker lived and worked is known as a time of upheaval in the internal life of the country. Fresh ideas and ideals were needed to lead the country out of the crisis. Confucius found such ideas and the necessary moral authority in the semi-legendary images of past history. He criticized his century, contrasting it with past centuries, and proposed his own version of the perfect man - Jun Tzu.

The ideal person, as constructed by the thinker Confucius, must have two fundamental characteristics: humanity (ren) and a sense of duty (yi). Humanity includes such qualities as modesty, justice, restraint, dignity, selflessness, and love for people. In reality, this ideal of humanity is almost unattainable. A sense of duty is a moral obligation that a humane person imposes on himself. It is dictated by the inner conviction that one should act this way and not otherwise. The concept of a sense of duty included such virtues as the desire for knowledge, the duty to learn and comprehend the wisdom of our ancestors. The undoubted merit of Confucius was that for the first time in the history of China he created a private school, with the help of which he spread classes and literacy.

“The path of the golden mean” is the methodology of Confucius’s reformism and one of the main links of his ideology.[5] The main questions addressed by Confucianism are: “How should people be governed? How to behave in society? The main theme in the thoughts of the Chinese sage was the theme of man and society. He built a rather coherent ethical and political doctrine for his time, which retained unquestioned authority in China for a long time. Confucius developed a system of specific concepts and principles with the help of which one can explain the world, and, acting in accordance with them, ensure proper order in it: “zhen” (philanthropy), “li” (respect), “xiao” (respect for parents) , “di” (respect for the elder brother), “zhong” loyalty to the ruler and lord) and others.

The main one among them is “zhen” - a kind of moral law, following which one can avoid unfriendliness, greed, hatred, etc. Based on them, Confucius formulated a rule, later called the “golden rule of morality”: “What you do not wish for yourself, do not do to others.” This maxim has taken its rightful place in philosophy, although it has been expressed in different ways.

The principle of “zhen” in the Confucian system correlated with another, no less important – “li”, which denoted the norms of communication and expressed the practical implementation of ethical law. People must follow this principle always and everywhere, starting with individual and family relationships and ending with state ones, thus introducing measure and orderliness into their actions. All the ethical requirements and guidelines of Confucius served to characterize a person who combined the high qualities of nobility, mercy and kindness towards people with high social status. The right path allowed us to live in complete harmony with ourselves and the world around us, without opposing ourselves to the order established by Heaven. This is the path (and ideal) of the “noble man”, to whom the sage contrasted the “little man”, guided by personal gain and selfishness and violating generally accepted norms. But, since people are equal by nature and differ only in habits, Confucius shows the “little man” the path to self-improvement: one must strive to overcome oneself and return to “li” - decency, respectful and respectful attitude towards others. In the 3rd century. BC. – II century The teachings of Confucius received the status of state ideology and subsequently became the basis of a specific Chinese way of life, largely determining Chinese civilization. Thanks to its simple and understandable ideas, as well as because of its pragmatism, Confucianism eventually became the state philosophy and religion of China. At the end of the Chunqiu period, when Lao Tzu lived, the main trend in the development of society was manifested in the fall of the slave system and the emergence of the feudal system. Finding himself face to face with the enormous social changes that were taking place, Lao Tzu rejected with disgust the principle of “government based on rules of behavior” that had prevailed in the former slave society and mournfully complained: “Rules of behavior undermine loyalty and trust, and give rise to unrest.” Lao Tzu (“Old Teacher”) is the ancient Chinese legendary founder of Taoism; according to legend, born in 604 BC[10] The followers of the “venerable teacher” outlined his main ideas in the book “Tao Te Ching” - “The Book of the Tao Path and the Good Power of Te,” also called “The Way of Virtue.” The main distinctive feature of the philosophy of Lao Tzu, which characterizes the followers of Taoism, is that Tao is considered as the source of the origin of all things, as a universal law governing the world, on the basis of which an ideological system arose, the highest category of which is Tao.

In contrast to the ethical and political views of Confucius, Lao Tzu reflects on the universe, on the global natural rhythm of events, using two basic concepts for this: “tao” and “de”. If for the founder of Confucianism Tao is the way of human behavior, the way of China, then for Taoists it is a universal worldview concept that denotes the beginning, basis and completion of all things, a kind of all-encompassing law of being. In “Shi Ji” (“Historical Notes”) by Sima Qian ( II-I centuries BC) provides the first classification of philosophical schools of Ancient China. There are six schools named there: “supporters of the doctrine of yin and yang” natural philosophers), “school of service people” (Confucians), “school of Mohists”, “school of nominalists” (sophists), “school of legalists” (legists), “school of supporters of the doctrine about Tao and Te” - Taoists. Later, at the turn of our era, this classification was supplemented by four more “schools,” which, however, with the exception of the zajia, or “school of eclectics,” actually have nothing to do with the philosophy of China. Some schools are named after the nature of the social activities of the founder of the school, others - after the founder of the teaching, and others - according to the main principles of the concept of this teaching. At the same time, despite all the specifics of philosophy in Ancient China, the relationship between philosophical schools ultimately came down to a struggle between two main tendencies - materialistic and idealistic, although, of course, this struggle cannot be imagined in its pure form. In the early stages of the development of Chinese philosophy, for example, even in the times of Confucius and Mozi, the attitude of these thinkers to the main question of philosophy was not expressed directly. Questions about the essence of human consciousness and its relationship to nature and the material world have not been defined clearly enough. Often, the views of those philosophers whom we classify as materialists contained significant elements of religious, mystical ideas of the past and, conversely, thinkers who generally occupied idealistic positions gave a materialistic interpretation to certain issues.

Heaven and the origin of all things. One of the important places in the struggle of ideas during the VI-V centuries. BC e. was occupied with the question of heaven and the root cause of the origin of all things. At this time, the concept of heaven included the supreme ruler (Shang-di), and fate, and the concept of the fundamental principle and root cause of all things, and at the same time it was, as it were, synonymous with the natural world, “nature,” the surrounding world as a whole. The ancient Chinese turned all their thoughts, aspirations and hopes to the sky, because, according to their ideas, personal life, the affairs of the state, and all natural phenomena depended on the sky (supreme). Many pages of not only “Shi Jing”, but also “Shu Jing” speak about the huge role of heaven in the life of the ancient Chinese, their belief in its power. The decline of the rule of the hereditary aristocracy was expressed in the decline of faith in the omnipotence of heaven. The former, purely religious view of the heavenly path began to be replaced by a more realistic view of the Universe surrounding man - nature, society. However, the basis of all religious superstitions was the cult of ancestors, for this cult constituted the genealogy of the ancient Chinese state. The ideology of Confucianism in general shared the traditional ideas about heaven and heavenly destiny, in particular, those set out in the Shi Jing. However, amid widespread doubts about heaven in the 6th century. before. n. e. Confucians and their main representative Confucius (551-479 BC) emphasized not on preaching the greatness of heaven, but on fear of heaven, of its punitive power and the inevitability of heavenly fate. Confucius said that “everything is initially predetermined by fate, and here nothing can be subtracted or added” (“Mo Tzu,” “Against the Confucians,” part II). He believed that “a noble husband should be afraid of heavenly fate,” and emphasized: “Whoever does not recognize fate cannot be considered a noble husband.” Confucius revered the sky as a formidable, all-unified and supernatural ruler, possessing well-known anthropomorphic properties. The sky of Confucius determines for each person his place in society, rewards and punishes. Along with the dominant religious view of the sky, Confucius already contained elements of the interpretation of the sky as synonymous with nature as a whole. Mo Tzu, who lived after Confucius, around 480-400. BC, also accepted the idea of faith in heaven and his will, but this idea received a different interpretation from him. Firstly, the will of heaven in Mo Tzu is cognizable and known to everyone - it is universal love and mutual benefit. Mo Tzu rejects fate in principle. Thus, Mo Tzu’s interpretation of the will of heaven is critical: the denial of the privileges of the ruling class and the affirmation of the will of the common people. Mo Tzu tried to use the weapons of the ruling classes, and even the superstitions of ordinary people of ordinary people, for political purposes, in the fight against the ruling class. The Mohists, having subjected to fierce criticism the views of the Confucians on the heavenly struggle, at the same time considered the sky as a model for the Celestial Empire. Mo Tzu's statements about the sky combine remnants of traditional religious views with an approach to the sky as a natural phenomenon. It is with these new elements in the interpretation of the sky as nature that the Mohists associate Tao as an expression of the sequence of changes in the world around man. Yang Zhu (6th century BC) rejected the religious elements of the Confucian and early Mohist views of heaven and denied its supernatural essence. To replace heaven, Yang Zhu puts forward “natural necessity,” which he identifies with fate, rethinking the original meaning of this concept. In the IV-III centuries. BC e. The cosmogonic concept associated with the forces of yang and yin and the five principles and elements - wuxing - is further developed. The relationship between the origins was characterized by two features: mutual generation and mutual overcoming. Mutual generation had the following sequence of principles: wood, fire, earth, metal, water; wood generates fire, fire generates earth, earth generates metal, metal generates water, water again generates wood, etc. The sequence of beginnings from the point of view of mutual overcoming was different: water, fire, metal, wood, earth; water overcomes fire, fire overcomes metal, etc. Back in the VI-III centuries. BC e. A number of important materialist positions were formulated. These provisions boil down to: 1) explaining the world as the eternal formation of things; 2) to the recognition of movement as an integral property of the objectively existing real world of things; 3) to finding the source of this movement within the world itself in the form of a constant collision of two opposing, but interconnected natural forces. 4) to an explanation of the change of diverse phenomena as the cause of a pattern subordinate to the eternal movement of contradictory and interconnected substantial forces. In the IV-III centuries. before. n. e. Materialistic tendencies in understanding the sky and nature were developed by representatives of Taoism. The sky itself in the book “Tao Tse Ching” is considered as an integral part of nature, opposite to the earth. The sky is formed from light particles of yang qi and changes according to Tao. “The function of heaven” is the natural process of the emergence and development of things, during which a person is born. Xun Tzu considers man as an integral part of nature - he calls the sky and its sense organs, the very feelings and soul of man “heavenly,” that is, natural. Man and his soul are the result of the natural development of nature. The philosopher speaks out in the harshest form against those who praise heaven and expect favors from it. The sky cannot have any influence on the fate of a person. Xun Tzu condemned the blind worship of heaven and called on people to strive to subjugate nature to the will of man through their labor. This is how the views of ancient Chinese philosophers about nature, the origin of the world, and the reasons for its changes developed. This process took place in a complex struggle between elements of natural scientific, materialistic ideas and mystical and religious-idealistic views. The naivety of these ideas and their extremely weak natural scientific basis are explained, first of all, by the low level of productive forces, as well as the underdevelopment of social relations.

Confucius set himself a twofold goal: 1) to streamline the relationship of kinship among the clan nobility itself, to streamline its mutual relations, to unite the clan slaveholding aristocracy in the face of the looming threat of its loss of power and its seizure by “inferior” people. 2) to justify the ideologically privileged position of the tribal nobility

Society and man Social and ethical problems were dominant in the philosophical reflections of the Chinese. In China, unlike Ancient Greece, cosmogonic theories were put forward not so much to explain the origin of the infinite variety of natural phenomena, earth, sky, but to explain the fundamental basis of the state and the power of the ruler.

Mo Tzu opposed inheritance of power based on the principle of kinship. For the first time in the history of China, he put forward a theory of the origin of state and power on the basis of a general agreement of people, according to which power was entrusted to “the wisest of people” regardless of his origin. In many ways, Mozi's views on the state echo the ideas of Plato, Epicurus, and Lucretius. Central to the teachings of the Mohists is the principle of “universal love,” which represents the ethical justification for the idea of equality of people and the demand of the free lower classes of ancient Chinese society for the right to participate in political life. In the teachings of Xunzi, the traditional ideas about the basis of government, expounded by Confucius and Mencius, were reinterpreted in the spirit of a compromise between ancient rituals and a single modern centralized legislation. At the end of the Zhou dynasty, a school of so-called legists (legalists) appeared. The legalists, whose main representatives were Tzu-chang, Shang Yang and Han Fei-tzu, resolutely opposed the remnants of clan relations and their main bearer - the hereditary aristocracy. Therefore, the Legalists criticized Confucianism no less sharply than the Mohists. The legalists rejected management methods based on ritual and tribal traditions, assigning the main role to uniform laws binding on everyone and the absolute, unlimited power of the ruler. They pointed to two sides of the law - reward and punishment, with the help of which the ruler subjugates his subjects. Legislation, a well-thought-out system of rewards and punishments, a system of mutual responsibility and general surveillance - this was what was supposed to ensure the unity of the state and the strength of the ruler’s power. The Legists shared Mozi's views on promoting talented people independent of rank and family relations with the ruler. Theoretically, the Legalists, like the Mohists, advocated equal opportunities for every person to rise in the country. Utopian views occupied a significant place in the history of ancient Chinese thought. The basis of ancient Chinese utopias about an ideal society were the ideas of egalitarianism and peace.

Schools of Indian philosophy.

By the 6th century. BC. in India, the prerequisites are emerging for an economic, political, social and, therefore, spiritual turning point in the development of the country - the emergence of the first states, a leap in the development of productive forces associated with the transition from bronze to iron, the formation of commodity-money relations, the growth of scientific knowledge, criticism of established moral ideas and attitudes. These factors served as the basis for the emergence of a number of teachings or schools, which are divided into two large groups. The first group is the orthodox philosophical schools of Ancient India, which recognize the authority of the Vedas. The second group is heterodox schools that do not deny the infallibility of the Vedas.

Don't compare yourself to others

Stop comparing yourself to others. It’s natural to compare your own and other people’s lives, but you shouldn’t do it too often. Otherwise, you risk starting to drag yourself down and worry that your life is not going the way it should. When comparing, it always seems that someone else’s life is somehow better. It is important to remember that we only see the lives of others superficially. We have no way of knowing what happens behind closed doors. Free yourself from worry and stop comparing yourself to others. Focus on your own life and how you feel about it. You'll be much happier this way.

What is the structure of the worldview?

Worldview structure is what a worldview is made of; what shapes it.

Thus, a worldview is formed from:

- your knowledge;

- ideas;

- principles (i.e. your point of view);

- convictions (steadfastness on any issue);

- ideals (your goals);

- spiritual and moral values (that which has no monetary value. This is what you consider extremely important based on your morality);

- life attitudes.

Always expect something good, not something bad.

Do you often focus your attention on the bad things that could happen in your life? You shouldn’t even think that something bad will happen to you. Life is too hectic and you often feel like you don't have enough time to do what others expect of you. As a result, your mood deteriorates and you are unhappy with your life. We tend to focus our attention on what can go wrong. Sometimes we like to complain, it starts to feel like complaining becomes second nature. Try to think about good things that can happen to you. Try not to complain for a week. Expect only the positive from every situation. You definitely won't be disappointed.

Three functions of worldview

Worldview is an integral part of human life as it guides a person.

Based on his worldview, a person makes decisions and acts .

- Cognitive function (or epistemological). Worldview is not only formed from our knowledge, but also gives us knowledge.

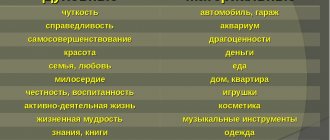

- Value-orientation function (axiological). This function is responsible for the formation of life values in a person.

- Practical function. Worldview influences a person's actions.

Worldview is the basis for a person’s way of thinking, his actions and actions.