Greetings, friends!

The main goal of philosophy has always been the desire to understand how the world works and what place a person occupies in it. At the same time, since ancient times, thinkers have wondered whether humanity will ever be able to find answers to all questions, or whether some aspects of the world order will remain unknown to us. We don’t know the answer to this question yet, so each version has its supporters.

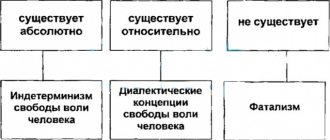

The concept according to which a complete understanding of the world is inaccessible to humans is called epistemological pessimism. Its supporters believe that the human mind is not capable of understanding all aspects of the world order, which means that there will always be questions to which humanity cannot find reliable answers.

Epistemological pessimism includes two directions:

- agnosticism is a philosophical concept according to which the world is unknowable to man, since some knowledge is inaccessible to him and will never be available;

- skepticism is a concept that questions the reliability of truth (that is, the very ability to reliably understand what is real and what is fiction).

Today we will talk about agnosticism. We will consider in detail the essence of this teaching, the history of its appearance and development, list the main supporters and analyze in detail how it differs from skepticism.

Essence[edit]

The main idea of agnosticism is that the world around us is unknowable in principle. There will always be at least something secret, and some questions are completely beyond the control of humanity - at least at the current stage of development. Specifically, religious agnosticism believes that questions regarding the existence of the Creator or the afterlife are beyond our control.

Often both atheists and believers do not like agnostics.

Some atheists believe that agnostics, with their uncertainty, only condone religion, since they admit the existence of God. Others believe that overly polite atheists often call themselves agnostics. To some, such delicacy seems unnecessary, given that reciprocal delicacy is not observed very often. In addition, people who try to take a position above the dispute between believers and atheists often mistakenly call themselves agnostics: “it is not known whether God exists or he does not exist.” But this is not agnosticism at all, but “weak” atheism: whoever thinks this way does not at all consider the question of the existence of God insoluble, he only believes that at the moment there is no answer to it. Well, dislike for people who, without any reason, try to take a position of intellectual superiority is quite understandable.

Believers do not like agnostics because they claim: if God exists, then he is such an unknowable, alien and powerful creature that it is almost impossible to solder him into the framework of existing religions. This is why many agnostics are often anti-clerical: the very idea of establishing social rules according to the opinion that some unproven being wishes it so seems incredibly stupid and even dangerous to them. However, some believers manage to successfully combine agnosticism with adherence to a specific religion, making ear tricks like “God, of course, is unknowable, but our great prophet prevailed/through apophatic theology we were able to...”

Ethical, legal and political views of Immanuel Kant

Kant thought a lot about man as a part of nature, about man as the ultimate goal of knowledge, and not as a means to achieve any goals, that is, he recognized the intrinsic value of man, the human personality. The thinker raised the question of the relationship between the concepts of “man” and “personality”. Kant is also known as the creator of the doctrine of transhistorical morality, independent of living conditions, common to all people. He created, as already mentioned, the doctrine of the so-called categorical imperative (law, commandment), which exists in the minds of people as an eternal ideal of behavior. The existence of such an imperative gives people freedom and at the same time jointly creates a universal moral law for society. Chekushkina E.N. Epistemology of morality by I. Kant // In the world of scientific discoveries. 2013. No. 1-1.S. 237-247. Thus, with regard to the problem of what is necessary and what is free in human activity, he believed that a conceivable discrepancy is given: a person acts out of necessity in one respect, freely in another. A person acts out of necessity, because he is placed by his thoughts and feelings under other natural phenomena and in this respect is subordinate to the necessity of the world of phenomena. At the same time, man is a moral being. As a moral being he belongs to the spiritual world. And as such, man is free. The moral law given only to reason is a “categorical imperative,” and the law to which every person must daily obey becomes a private moral law for every living person. If the act of an individual does not comply with the universal moral law, but is performed by a person on the basis of his own inclinations and desires, it cannot be called moral. Human actions are moral only when they are performed in accordance with the universal moral law (imperative). Fulfilling the imperatives of the universal moral law, a person may feel unhappy, that is, he does not receive empirical happiness, so a person’s moral consciousness often experiences discord caused by the discrepancy between a person’s moral behavior and the expected result. Therefore, happiness does not belong to the world of things, but to the world of the spiritual. “Happiness is the state of a rational being in the world when everything in its existence happens according to its will and desire” Kant I. Criticism of the practical concept. - M.: Librocom, 2012. - 194 p. . But for this to be so, a person must achieve a high degree of morality so that his will and desires do not contradict the categorical imperative. Individual imperatives may be hypothetical, that is, the implementation of this or that rule may contribute to a person’s success in his profession, in society, but the main moral imperative stands above them. It produces actions that are certainly good: Honesty, courage, nobility and many others. If a person directs his will and desires towards them, he will experience true happiness through their fulfillment and achievement. At the same time, man achieves the highest goal of his existence. From this point of view, a person can also be considered as a “thing in itself” and a phenomenon. When people obey only a hypothetical imperative, that is, do “good” in order to achieve material wealth, empirical happiness, they become a phenomenon. And only by acting in accordance with the dictates of the categorical imperative, sometimes to the detriment of their empirical happiness, do they become a “thing in itself”, acquire essence and a partial possibility of knowing themselves. This highest, non-empirical happiness is embodied in virtue, the highest value of being. Thus, Kant placed moral principles above the practical interests that prevailed in the capitalist society of his contemporaries. This was the highest achievement of Kant's ethics, its guiding humanistic value. He openly declared that man is the highest value, and that the education of morality and virtue in man is the main task of philosophy and pedagogy.

Concept of agnosticism

Definition 1

Agnosticism is one of the philosophical concepts according to which the world cannot be known. That is, people cannot know anything reliably about God or gods, or about the actual essence of things.

Proponents of agnosticism considered it fundamentally impossible to know any ultimate and absolute foundations of reality. They also completely deny the possibility of proving or disproving ideas and statements based on subjective premises.

In addition to philosophical agnosticism, there is also theological and scientific agnosticism. Agnostics in theology separate the cultural and ethical component of faith and religion, considering it a kind of secular school of moral behavior in society, from the mystical one, which touches on the problems of the existence of gods, demons, the afterlife and religious rituals, without attaching significant significance to them. Scientific agnosticism exists as a principle of the theory of knowledge, suggesting that since the experience gained in the process of cognition will inevitably be distorted by the consciousness of the subject. At the same time, the subject is fundamentally unable to comprehend an accurate and complete picture of the world. This principle does not deny knowledge, but only indicates the fundamental inaccuracy of any knowledge and the impossibility of complete knowledge of the world.

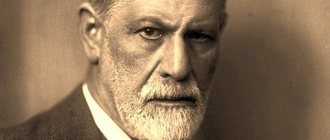

The main ideas of agnosticism were formulated in the works of Kant, Hume and Berkeley.

Note 1

Agnosticism completely denied the possibility of knowing the material, objective world, of knowing the truth, and rejected objective knowledge.

In relation to God, agnosticism denies the possibility of knowing God, that is, obtaining knowledge or any reliable information about God, and even more so even the very possibility of resolving the question of the existence of God is denied.

Differences between agnosticism and skepticism

The ideas of agnosticism were first expressed by ancient skeptics, so we can assume that it comes from skepticism. And yet the difference between them is quite significant, so it is impossible to identify them or consider one part of the other.

Skepticism comes from the fact that it is impossible to reliably understand what knowledge corresponds to objective reality and what does not. Agnosticism allows such an understanding, but at the same time considers the very ability of the human mind to understand the metaphysical foundations of reality to be limited. Thus, agnosticism limits the potential of cognitive processes, while skepticism essentially questions their value.

Huxley emphasized that as science develops, the boundaries of knowledge expand, but some questions always remain outside these boundaries and, apparently, many will always remain there. In particular, from Huxley's point of view, it is impossible to reliably confirm or disprove the existence of God and other supernatural entities.

In this regard, the difference between agnosticism and skepticism is that the first implies a clear understanding of where the boundaries of reliable knowledge lie, while the second generally denies the possibility of distinguishing reliable knowledge from unreliable knowledge.

Philosophical agnosticism

The beginnings of agnosticism can be seen in the teachings of ancient philosophers. Thus, the ancient Greek philosopher Protagoras (485-410 BC) argued that, we quote: “man is the measure of all things.” Because All people are different and perceive the world around them differently; objective truth as such cannot exist in principle. In one aspect or another, representatives of different philosophical movements - positivism, empiricism, evolutionism and others - used agnosticism in their teachings in later periods.

The most famous agnostic philosophers:

- George Berkeley (1685-1753).

- David Hume (1711-1776).

- Immanuel Kant (1724-1804).

- Herbert Spencer (1820-1903).

Let us dwell in more detail on the views of some of the most prominent representatives of this trend in philosophy.

George Berkeley

George Berkeley argued that “being is that which is perceived, or the one who perceives.” Thus, the entire surrounding world is mediated by human perception, and exists in the human mind only in the form in which people perceive it.

Accordingly, any knowledge of the surrounding world is mediated by human perception, and therefore cannot be absolute. Thus, the only reality for a person can only be his own consciousness and perception of the world around him.

David Hume

David Hume expressed many similar ideas. In his “Treatise of Human Nature,” Hume pays a lot of attention to the topic of the reliability of knowledge as such and the ability to be convinced of the correctness of a particular message. This does not mean total skepticism, but it does indicate the need to clear the cognitive space as the first step towards knowledge, at least relative.

According to Hume, any knowledge is built on experience gained through sensory perception, and is supplemented by a person’s own conclusions made in the process of gaining experience. Thus, the process of cognition is always associated with certain assumptions and even fantasies, which cannot always be verified experimentally.

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant believed that the surrounding world exists as a “thing in itself,” i.e. regardless of our consciousness, influencing a person and his senses. Therefore, the key question becomes the study of the mind itself and its boundaries, because This directly determines whether pure knowledge is possible and how pure knowledge is possible.

Kant believed that until we understand this, we cannot know how similar the “thing for us” (what we see) is to the “thing in itself” (what exists in reality). This is the agnosticism of Kant, who actually took the position of the impossibility of absolute knowledge as long as the capabilities of the human mind are unknown.

Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer in his work “Fundamentals” argues that a person cannot know anything about the so-called “ultimate reality”, i.e. one that goes beyond the capabilities of the human mind at this stage.

Religion takes advantage of this, explaining various phenomena with the help of conjectures and metaphors, which, again, are not possible to verify due to the limitations of human cognition. However, such limited possibilities of knowledge does not at all mean the absence of evolution, progress of human society, human thought and science.

Thus, agnosticism in philosophy is the understanding that a person cannot know anything about God and other phenomena that cannot be studied experimentally. This approach is also valuable for science.

The origin and development of agnosticism

As noted above, the first arguments in favor of agnosticism were expressed by ancient philosophers, adherents of skepticism. Their main argument was the imperfection of the knowledge available to humanity, which was constantly changing and revised. In this regard, skeptics refused to consider any existing knowledge as true and relativized it (relativism is a philosophical concept that affirms the relativity, conventionality and subjectivity of human cognition), arguing that they do not reflect objective reality, but the available methods of cognition.

In a relatively modern form, the main ideas of agnosticism were formulated by George Berkeley. He argued that a person is not able to go beyond the limits of his own sensory knowledge, which means that a full understanding of objective reality is not available to him.

David Hume and Immanuel Kant are considered the authors of the classical concept of agnosticism. Hume argued that any knowledge a person has comes from experience. And this experience will always be limited, and it is impossible to go beyond its limits. Accordingly, it is impossible to reliably understand how knowledge coincides with objective reality. Kant applied the concepts of “thing in itself” and “thing for us” to objective reality. He believed that a subject can perceive in any object only the meaning that he puts into it through his own actions.

A significant role in the development of the doctrine was played by the analysis of Victor Cousin’s reasoning about the nature of God and its knowability, which was published in 1829 by William Hamilton. Subsequently, many of the thoughts expressed in this work were repeated by one of the main representatives of agnosticism, Herbert Spencer.

Based on Kant's ideas, Hamilton believed that all knowledge a person can have is based on subjective experience. And knowledge that is outside of experience will always remain antinomic for a person (antinomy is a situation in which two mutually contradictory statements look equally valid from the point of view of logic).

What is the difference between an atheist and an agnostic

Both concepts reject the existence of a higher power, they have their own differences that are worth paying attention to:

| Atheist | Agnostic |

| Consciousness is closed. There is no change in belief. This is a mature, formed personality who adheres to beliefs and views | Consciousness is open. May change point of view throughout adult life. Open to exploring new and unknown things |

| Egoist - denies the existence of Higher powers | Humanist – treats loyally. Believers have a special meaning |

| Lack of soul. No afterlife | Feel the presence of the human soul inside |

| No religious holidays | Accepts gifts for Christmas and Easter. May celebrate religious holidays |

A large number of differences does not mean that there are no similarities in both concepts:

- sensible people who put reason at the forefront. The action must have a logical conclusion;

- a clear understanding of the world;

- it is impossible to prove the existence of God. Even if there is confirmation in the Bible;

- faith - there is no specific process.

It is everyone’s right to believe or not in the existence of the Supreme. In order to know exactly the version that a person adheres to, you need to determine the presence of negations.

Watch a video about the differences between the concepts of an atheist and an agnostic:

What do agnostics believe?

Agnostics see the human world in their own way. In order to correctly understand the essence of agnosticism, it is necessary to understand what exactly representatives of time agnosticism believe:

- Man cannot understand the world and its phenomena;

- Regarding religion, it is impossible to accurately determine whether God exists or not. That is, such a religious concept cannot be either proven or disproved by man;

- It is impossible to accurately determine the boundaries of good and bad. That is, the eternal debate about good and evil is ineffective and will not bring any results;

- All confirmed knowledge can always be refuted in the future. This means that knowledge is not valid;

- At the same time, agnostics do not refute the possibility that someday humanity will be able to unambiguously determine the existence of certain phenomena.

Agnostics hold certain beliefs and positions

Definition of agnosticism

Primarily a scientist, Huxley presented agnosticism as a form of demarcation. A hypothesis without supporting, objective, testable evidence is not an objective scientific statement. Thus, it would not be possible to test the stated hypotheses, leaving the results inconclusive. His agnosticism is incompatible with forming a belief in the truth or falsity of a given statement. Karl Popper would also call himself an agnostic. According to philosopher William L. Rowe, in this strict sense, agnosticism is the view that human reason is incapable of providing sufficient rational reasons to justify either belief in the existence of God or belief that God does not exist.

George H. Smith, recognizing that the narrow definition of atheist was the generally accepted definition of the word, and recognizing that the broad definition of agnostic was the common definition of the word, contributed to broadening the definition of atheist and narrowing the definition of "atheist". agnostic. Smith rejects agnosticism as a third alternative to theism and atheism and promotes terms such as agnostic atheism (the view of those who do not believe

into the existence of any deity, but does not claim to

know whether the deity exists

or not) and agnostic theism (the view of those who do not claim to

know

of the existence of any deity, but still

believe

in such an existence).

Etymology

Agnostic

(from Ancient Greek

ἀ-(a-)

"without" and

γνῶσις (gnōsis)

"knowledge") was used by Thomas Henry Huxley in a speech at a meeting of the Metaphysical Society in 1869 to describe his philosophy, which rejected all claims to spiritual or mystical knowledge.

Early Christian church leaders used the Greek word gnosis

(knowledge) to describe "spiritual knowledge". Agnosticism should not be confused with religious views opposed in particular to the ancient religious movement of Gnosticism; Huxley used the term in a broader, more abstract sense. Huxley defined agnosticism not as a creed, but rather as a method of skeptical, evidence-based inquiry.

In recent years, the scientific literature on neuroscience and psychology has used the word to mean “unknowable.” In technical and marketing literature, the term "agnostic" can also mean independence from some parameters, such as "platform independent" (refers to cross-platform software) or "hardware independent".

Qualifying agnosticism

Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume argued that significant statements about the universe are always subject to some degree of doubt. He argued that people's fallibility means that they cannot obtain absolute certainty except in trivial cases where the statement is true by definition (for example, tautologies such as "all bachelors are unmarried" or "all triangles have three angles") .

Types

Strong agnosticism (also called "hard", "closed", "strict" or "persistent agnosticism") The view that the question of the existence or non-existence of a deity or deities, and the nature of ultimate reality, is unknowable due to our natural inability to verify any experience with something other than other subjective experience. A strong agnostic would say, “I can’t know whether a deity exists or not, and neither can you.” Weak agnosticism (also called "soft", "open", "empirical" or "temporal agnosticism") The view that the existence or non-existence of any deities is currently unknown, but not necessarily unknowable; therefore, no one makes a judgment until the evidence, if any, comes out. A weak agnostic would say, "I don't know whether there are any deities or not, but maybe one day, if there is evidence, we can find out something." Apathetic Agnosticism The view that no amount of debate can prove or disprove the existence of one or more deities, and that if one or more deities exist, they do not seem to care about the fate of people. Consequently, their existence has virtually no effect on personal human affairs and should not be of particular interest. An apathetic agnostic would say, "I don't know whether any deity exists or not, and I don't care whether there is one or not."

Subcategories of agnosticism

Agnosticism has 4 subcategories:

- Weak. For adherents of weak or temporary agnosticism, the question of the study of God has no answer. They are convinced that this is not accessible to the human mind.

- Strong. It is also called absolute or strict. Agnostics of this school consider proof of the existence or non-existence of God impossible, since none of the theories can be tested.

- Indifferent. Adherents of the indifferent direction consider the very question of the existence or non-existence of God to be unimportant. It is based on the belief that neither theists nor atheists have convincing evidence, so there is no point in discussing this topic.

- Ignosticism. Representatives of this movement are interested not only in the very possibility of the existence of God. First of all, they strive to give a precise definition of the concept of “God”. Until the scientific community has a clear definition for the object of research, it is impossible to begin studying it.

Often, agnostics do not affiliate themselves with a specific group, calling themselves simply agnostics, without elaboration.

How agnostics see the world - examples

A person who can say to himself: “I am an agnostic” sees the world as new knowledge endlessly opening up to him. He believes that if any evidence or theory can be refuted and proven invalid over time, then the same can happen with any other knowledge.

For example, people have long been convinced that the Earth is flat and rests on a turtle and three whales. This was a completely plausible theory, because everyone, looking around, noticed that the plane was really flat. And the stories of travelers that there is an edge in the sea, over which the water flows far down, only confirmed the guesses.

But over time, the theory of a flat Earth was destroyed, people saw evidence of the spherical shape of the planet and believed in it. The previous knowledge, which was believed in for a long time, has collapsed.

It's the same story with matter. It is generally accepted that the entire surrounding reality consists of the smallest particles - atoms. And no one doubts this. But as soon as scientists were able to create a more powerful microscope and see that the atom was made up of even smaller particles, the theory collapsed.

It turns out that you can change your beliefs ad infinitum. It is only a matter of time and technological progress.

Immanuel Kant - founder of German classical philosophy

An interesting fact: the outstanding philosopher Immanuel Kant was born in the Russian city of Kaliningrad, which was then called Koenigsberg. This significant event took place on April 22, 1724. But on that day, no one could have predicted the future glory of the son of a simple artisan and housewife. The fourth child among eleven siblings, little Kant grew up in poor health but with a quick mind. When his parents noticed this, they sent young Immanuel to school at the age of 9. Almost immediately the boy showed a keen interest in history and Latin. Although the main subject - theology - did not seem so interesting to him. But what most surprised the thinker’s biographers was that in high school Kant did not show the slightest interest in philosophy. His studies were mediocre, but he always learned strict discipline. After graduating from the gymnasium in 1740, Kant entered the theological faculty of the University of Königsberg, which was founded in 1544 and had a long academic tradition. However, he soon realized that he had made a mistake, as he developed an unexpected interest in philosophy, mathematics, physics, anthropology, philology, medicine and many other sciences. Perhaps this was due to the spirit that reigned in this ancient center of science. The young scientist planned to defend his master's thesis in philosophy, but the death of his father prevented this. To support his younger brothers and sisters and himself, Kant got a job as a private tutor and worked there for 10 years. It was during this period that he conducted active scientific work, rethinking the scientific worldview of the era. Cassirer E. The Life and Teachings of Kant. - M.: Center for Humanitarian Initiatives, 2013. - 448 p. A number of outstanding scientists of the Enlightenment, such as Copernicus (1473-1533), Spinoza (1632-1677), Hobbes (1588-1679), Locke (1632-1704), Leibniz (1646-1716), Newton (1642-1727), shook the medieval scientific ideas that had long dominated in Europe. Gradual but important changes took place in society: emerging capitalism began to resist absolutism and feudalism. Production became more efficient and required the development of applied sciences. Applied sciences, especially mechanics, also influenced the development of abstract scientific disciplines. The discoveries of Copernicus, Leibniz, Newton, Kepler (1571-1630) and others created a real scientific revolution. Heliocentric theory replaced geocentrism, materialistic metaphysics replaced religious scholasticism, philosophy ceased to serve only theology, but began to develop as an independent discipline. At the same time, people's worldview was liberated: the values of reason and pragmatism came to the fore, and the romantic ideals of chivalry and monasticism were relegated to the background. People awakened to a thirst for knowledge about the study of society, a need to explain the world around them from a scientific and philosophical point of view, separated from theological concepts. It should be noted that these trends were not yet purely atheistic. The term "God" has been used in both philosophy and theology. But philosophy interpreted it as a completely new category, identifying it with the “higher mind” and “nature”. Thinkers of the Enlightenment era (late 17th-18th centuries) tried to see through the accumulation of dogmas and elements of the cult of the “true God” the nature of harmonious relationships in the triangle “God-Nature-Man”. At the same time, society was not yet ready to accept this “harmony”, which was too full of freedom of thought and equality. Religious conflicts gave way to wars for political power. There was an urgent need for the formation of a new rationalistic, but at the same time humanistic philosophy, with a new look at society, state and law, ethics, science, culture, religion, etc. Gryadovsky D.I. History of philosophy. Book 3.

Kant's pedagogical activity

During his teaching career from 1747 to 1755. Kant was actively engaged in self-education and observation of human characters and the peculiarities of social relations in Prussia at that time. Based on the cosmogonic teachings of Newton, I. Kant put forward a revolutionary theory of the emergence of the Solar system from a cosmic nebula, as well as a theory of the dynamic evolution of the Universe, which has not lost its relevance to this day. Kant understood the formation of stars and planets as a result of the friction of attracting and repulsive particles. By studying the structure of the Universe only from the point of view of mechanics, Kant largely managed to get ahead of the astronomical science of his time, which indicated the undoubted genius of the scientist. Of course, there were shortcomings in his theory, but they cannot be assessed strictly from the point of view of the undeveloped scientific ideas of the time. In 1755, Kant presented two dissertations to the University of Königsberg, one of which he defended and successfully passed the exam for admission to the Faculty of Philosophy. He later received the title of privatdocent - a freelance lecturer who could charge students money for his lectures. To earn money in such a position, considerable talent was required, because it was necessary to keep the students’ attention precisely on his lectures. And Kant successfully coped with this task. He then taught for 41 years, attracting continued interest and reputation among young people. Lectures on logic, metaphysics, mathematics, and natural sciences alternated with lectures on geography, mechanics and ethics. Later exotic disciplines such as fortification and pyrotechnics were added, which were freely subject to Kant's encyclopedic mind. Narsky I. S. Kant. - M.: Book on Demand, 2012. - 208 p. After the Seven Years' War, Kant was a Russian subject for some time, which again linked his fate with Russia. From 1770 he received an official position at the university department. Gradually he managed to earn a fortune, but teaching took a lot of energy, leaving Kant little time for philosophical activity. However, Kant used even these “crumbs” surprisingly effectively. The thinker clearly planned every day, allocating estimated hours for intellectual work and reflection. Kant was most interested in problems of metaphysics, morality, religion and anthropology. The pre-critical period of his work (1744 - 1770) was marked by increased interest in pre-philosophical issues. In particular, as we noted above, Kant created his own cosmogonic system, dealt with issues of classification of animals, problems of the origin of human races, and some natural phenomena. In the immediate philosophical, so-called critical period of his work, Immanuel Kant devoted himself to developing his epistemological and metaphysical teachings. His mind was occupied with questions of knowledge and existence, morality, aesthetics and law. In 1781, his famous work “Critique of Pure Reason” was published, then “Critique of Practical Reason” (1788) and “Critique of Judgment” (1790) and a number of other works appeared. In them, the thinker raised the most important issues of epistemology, ethics and aesthetics and gave the world his original view of these problems, which influenced the further development of philosophy. Such basic concepts of Kant’s philosophy as “thing in itself”, “Anschauung”, “apriori”, “transcendentalism”, “antinomy”, “expediency”, “value”, etc. appeared and became firmly established in the terminology of philosophy. Polikarpova E.V. . Kant and the foundations of intellectual and political liberalism // History of State and Law. 2012. No. 15.S. 12-18. Thus was born classical German philosophy - a child of the German Enlightenment, which gave the world two new ideas: the active nature of man and continuous development.

Who is it

The incomprehensibility of the term agnostic and who it is can be explained in simple words as the presence of constant human doubts about the truth of the facts. This is someone who will not believe someone else's experience or views without objective, scientific evidence provided. This is materialism, but at the same time, the agnostic does not deny the presence of the spiritual world and the influence of energies on human development, he only waits for real evidence before asserting this. Such people are characterized by high intelligence, which makes them constantly doubt, analyze the universe in its entirety and each time come to the conclusion of how small human capabilities are, as well as life expectancy, in order to really comprehend what is happening in world processes at the global level (and this is even necessary to explain the functioning of our cells).

Agnostics deny only the mystical side of faith and religion, while supporting its influence on the value-semantic and spiritual space of the individual, on the formation of its internal structure, as well as the regulation of actions. An agnostic views any religion not as a set of beliefs and statements about the existence of the invisible world, but as a model for building life, a certain set of norms and rules, guided by which a person continues his path. This applies to any information that is not accepted as a starting point, because any knowledge changes the subjective picture of the world and then the personality undergoes changes, and under these changes there is also a transformation of interpretation. As a result, through many layers of subjective perception, there is no real idea of anything, which is what the agnostic is talking about.

The only religions that can bypass agnosticism in its critical attitude are Buddhism and Taoism, since in them there is no interpretation of the person of God, but only a set of proposed rules for building one’s life. Faith, as a guide to the optimal construction of internal ethical standards, is quite suitable for an agnostic, so if they are carried away by some kind of faith, then usually these are teachings about energies, interaction and the like, where there is no personification.

The connection between agnosticism and religion

Agnosticism is mistakenly considered a religious belief. But this is a misunderstanding of the essence of the direction. The teaching of agnostics does not deny the existence of gods, but does not consider religions to be a reliable source of knowledge about the highest principle. It denies the possibility of proving the truth of statements using the rational approach that guides scientists in the process of studying any hypothesis.

An agnostic can believe in God, but being an adherent of a particular religion cannot. Dogmatic religions leave no room for doubt, and contradict the agnostic belief in the impossibility of knowing the world. Therefore, belief in God can only be a vague belief in an idea, and not a specific object.

In some religions, the definition of god is given briefly or not at all. In Buddhism and Taoism, the absence of a personified god avoids the conflict between religion and agnosticism.

Agnosticism in the history of philosophy

In philosophy, agnosticism is not called an independent concept, but a general skeptical position in knowledge: both doubt about the adequacy of the methods available to humans, and epistemological pessimism regarding objective reality in general. Such views were formulated in various forms in a variety of philosophical schools. For example, Kant’s subjective idealism considers knowledge of objective entities to be fundamentally impossible for the subjective mind, and positivism asserts the meaninglessness of asking questions that go beyond the limits of what is accessible to empirical verification.

For the first time, the agnostic tendency was voiced by the Greek sophists: Protagoras taught that “everything is as it seems to us” (in the spirit of epistemological relativism), and Gorgias formulated a kind of manifesto of agnosticism: “Nothing exists; but even if something exists, it is unknowable; but even if it is knowable, it is inexplicable for another"

.

Empirical philosophers pointed out that the experience we acquire introduces us only to sensations, and not to the things themselves. D

Hume therefore concluded that we cannot know not only how much subjective perception corresponds to objective reality, but even whether it exists at all outside of our sensations. I. Kant, in his Critical Philosophy, postulated the existence of objective “things-in-themselves” (essences, noumena), real sources of our sensations, but considered subjective sensory experience to be the only form of knowledge, and therefore concluded that knowledge is fundamentally limited by the structure of the cognitive capabilities of the subject himself: we cannot cognize a real object, but only how it appears in human experience - a phenomenon (“thing-for-us”, phenomenon).

Agnosticism ignores the fundamental imperative for philosophy to search for a universal objective basis, and therefore is subject to constant criticism both from the positions of religious philosophy and from the positions of materialism, which see such a basis in God and in matter, respectively. Thus, Leo Tolstoy wrote: “I say that agnosticism, although it wants to be something special from atheism, putting forward the imaginary impossibility of knowing, is in essence the same as atheism, because the root of everything is the non-recognition of God.” And V.I. Lenin, discussing the opposition of materialism and idealism, on the contrary, reproached agnosticism for intellectual indecisiveness and reactionaryness: “Agnosticism is an oscillation between materialism and idealism, that is, in practice, an oscillation between materialist science and clericalism. Agnostics include supporters of Kant (Kantians), Hume (positivists, realists, etc.) and modern “Machians.” In dialectical materialism, the epistemological basis of agnosticism was the absolutization of relativity, and its historical prerequisite was the conflict of religious and scientific worldviews, the desire to avoid this alternative, or an attempt to synthesize them.

Origins of agnosticism

Initially, the divine component in this philosophical teaching was practically absent. The first prerequisites for the emergence of agnosticism were doubts that arose regarding the absoluteness of knowledge and the variability of the world as such. “I only know that I know nothing” - fit well into the concept and largely defined it.

In a word, the philosophical foundation of this worldview was laid by ancient agnostics. Representatives of that time, such as Socrates or the same Protagoras, not to mention the sophists and skeptics, spoke only about the impossibility of a complete penetration into the essence of things as such. Only later, over time, did God emerge in the paradigm of the phenomena they studied.

Famous agnostics

Among the representatives of agnosticism one can single out Protagoras, Kant and Hume, the greatest Scottish philosopher. Among his contemporaries, Hume became famous for his political and diplomatic activities. Hume served as a diplomat at the British embassy in France, and in addition to his main work, he was engaged in writing scientific works. He published a fundamental collection of works - the collection “History of England”, which quickly spread throughout all countries of Western Europe.

Under the influence of Hume's views that spread among the intellectual elite, the next generation of agnostics was formed:

- A. Smith;

- O. Comte;

- O. Comte;

- B. Russell.

According to Hume, knowledge must be based on sensations and experience. The philosopher also assumed the existence of non-experimental knowledge, the classical type of which he called mathematics. Mathematical science appeared as a result of the activity of consciousness, and it, unlike perception, is subjective.

Bibliography

- Abdildin Zh.M.: Dialectics of Kant. - M.: Book on Demand, 2012. - 160 p.

- Gryadovsky D.I. History of philosophy. Book 3. European Enlightenment. Immanuel Kant. - Edinstvo-Dana Publishing House, 2011 - 472 p.

- Deleuze J. Empiricism and subjectivity. - MOSCOW: PER SE, 2011. - 480 p.

- Cassirer E. The Life and Teachings of Kant. - M.: Center for Humanitarian Initiatives, 2013. - 448 p.

- Kant I. Critique of practical reason. - M.: Librocom, 2012. - 194 p.

- Kant I. Critique of Pure Reason. - M.: Eksmo, 2012. - 736 p.

- Kant I. Outlines of the metaphysics of morals. - M.: Mysl, 2001. - 1472 p.

- Minasyan L.A. Transcendental philosophy and post-non-classical science: rereading Kant // Scientific thought of the Caucasus. 2005. No. 4. P.21-30.

- Narsky I.S. Kant. - M.: Book on Demand, 2012. - 208 p.

- Nikitina I.P. Aesthetics. - M.: Yurayt, 2013 - 680 p.

- Novgorodtsev N. Kant and Hegel in their teachings on law and state. - M.: Book on Demand, 2013 - 253 p.

- Polikarpova E.V. Kant and the foundations of intellectual and political liberalism // History of State and Law. 2012. No. 15. P.12-18.

- Samylov V. Formation of the principle of historicism in German classical philosophy (Kant and Hegel) // Social and humanitarian knowledge. 2012. No. 4. P.56-67.

- Semenov E.V. Transcendental semantics of I. Kant // Questions of Philosophy. 2011. No. 11. P.152-162.

- Serdechna V.V. Doctrines about knowledge in the English tradition // Context and reflection: philosophy about the world and man. 2012. No. 2-3. P.76-94.

- Chekushkina E.N. Epistemology of morality by I. Kant // In the world of scientific discoveries. 2013. No. 1-1. P.237-247.

- Shashkevich P.D. Empiricism and rationalism in the philosophy of modern times. - M.: Book on Demand, 2012. - 304 p.

Agnosticism in the history of philosophy

In philosophy, agnosticism is not called an independent concept, but a general skeptical position in knowledge: both doubt about the adequacy of the methods available to humans, and epistemological pessimism regarding objective reality in general. Such views were formulated in various forms in a variety of philosophical schools. For example, Kant’s subjective idealism considers knowledge of objective entities to be fundamentally impossible for the subjective mind, and positivism asserts the meaninglessness of asking questions that go beyond the limits of what is accessible to empirical verification.

For the first time, the agnostic tendency was voiced by the Greek sophists: Protagoras taught that “everything is as it seems to us” (in the spirit of epistemological relativism), and Gorgias formulated a kind of manifesto of agnosticism: “Nothing exists; but even if something exists, it is unknowable; but even if it is knowable, it is inexplicable for another"

.

Empirical philosophers pointed out that the experience we acquire introduces us only to sensations, and not to the things themselves. D. Hume therefore concluded that we cannot know not only how subjective perception corresponds to objective reality, but even whether it exists at all outside of our sensations

I. Kant, in his Critical Philosophy, postulated the existence of objective “things-in-themselves” (essences, noumena), real sources of our sensations, but considered subjective sensory experience to be the only form of knowledge, and therefore concluded that knowledge is fundamentally limited by the structure of the cognitive capabilities of the subject himself: we cannot cognize a real object, but only how it appears in human experience - a phenomenon (“thing-for-us”, phenomenon).

Agnosticism ignores the fundamental imperative for philosophy to search for a universal objective basis, and therefore is subject to constant criticism both from the positions of religious philosophy and from the positions of materialism, which see such a basis in God and in matter, respectively. Thus, Leo Tolstoy wrote: “I say that agnosticism, although it wants to be something special from atheism, putting forward the imaginary impossibility of knowing, is in essence the same as atheism, because the root of everything is the non-recognition of God.” And V.I. Lenin, discussing the opposition of materialism and idealism, on the contrary, reproached agnosticism for intellectual indecisiveness and reactionaryness: “Agnosticism is an oscillation between materialism and idealism, that is, in practice, an oscillation between materialist science and clericalism. Agnostics include supporters of Kant (Kantians), Hume (positivists, realists, etc.) and modern “Machians.” In dialectical materialism, the epistemological basis of agnosticism was the absolutization of relativity, and its historical prerequisite was the conflict of religious and scientific worldviews, the desire to avoid this alternative, or an attempt to synthesize them.

Agnosticism as a worldview

Agnosticism is not just a special attitude to the issue of faith and religion, it is a separate type of worldview, located between belief in the supernatural and a scientific view of the world. For an agnostic approach, it is important to accept the existence of God, but to question any evidence for his existence.

Agnostic ethics does not allow dogmatism. This is not a separate paradigm, but an intellectual position. Anyone who considers himself an agnostic must view religion from a logical perspective. To be an agnostic is to be a skeptic. Representatives of every philosophical school based on the idea of denying absolute knowledge can be classified as agnostics. At the same time, the teachings themselves can differ radically from each other.

Agnostic - who is it? General concept of the term

Agnostics are people who adhere to agnosticism. The word comes from the ancient Greek “”, which translates as “unknowable”, “unknown”. People who consider themselves agnostics adhere to the theory of the impossibility of knowing the axiom of the existence of any gods, and therefore they do not consider themselves to be a member of any of the existing faiths. A distinct feature from atheism is that agnosticism does not deny the possible existence of divine quintessences.

History of the emergence of ideology

The first mentions of agnosticism date back to the philosophy of antiquity (late 7th – 6th centuries AD), where the ancient Greek philosopher Protagoras, a representative of the philosophical movement of the sophists, argued that our consciousness is relative and subjective. His ancient Indian contemporary supported agnostic views on existence and believed that after death some kind of life awaits us.

The definition was first given by Thomas Henry Huxley, an English zoologist, in 1869. He was the first to officially express the opinion that he could not and did not intend to identify himself with any of the existing religions. In his opinion, an agnostic is a person who does not deny the existence of a higher power, but also will not accept the existence of any specific god. While the agnostic does not deny, he also does not confirm the existence of gods, believing that the primary is unidentified and therefore unknown.

The ideas of agnosticism became widespread among English naturalists in the 19th century.

Agnosticism in general

Agnostics deny the existence of any specific truth, and argue that the world around us cannot be known objectively. According to the concept under discussion, we cannot know anything about divine manifestations, about God, the afterlife and other life, because our knowledge cannot be confirmed by the evidence of experimental science.

In other words, we do not have irrefutable evidence of the existence of divine forces, but we also have no evidence that these forces do not exist. It is not possible to prove the presence of a soul by scientific methods, either at the present moment in the development of mankind, or in general.

With all of the above, an agnostic can be both a believer and an unbeliever. For adherents of agnostic philosophy, the very idea of arguing about the existence or non-existence of higher powers is unnecessary.

What is the difference between an agnostic and an atheist?

Agnostics are sometimes confused with atheists. The interweaving of these philosophical currents is fundamentally wrong. Atheists vehemently deny the existence of God, while agnostics withhold judgment. They don't know because nothing has been proven.

Atheism is not opposed to any particular faith: the atheist is equally skeptical of the Christian God and Zeus. In a similar way, agnostics relate to manifestations of deity - equally to Allah and the Torah. They do not recognize the manifestation of “miracles” if they contradict the laws of nature.

Relationship between agnosticism and other religions

The atheists mentioned above are distrustful of agnostics for their “vagueness.” Adherents of atheism believe that the question “Do you believe in God?” there are only two answer options, while agnostics choose the third. According to the first, if the answer is “no,” then you are automatically an atheist, and if “no,” then you are a believer by designation.

Exclusively religious people consider agnostics to be banal “lazy people” who can cross themselves at a difficult moment in life, but will never come to church on Sunday. Considering that faith is based not only on the Bible, but also on personal experience, believers often try to turn agnostics to their side by telling stories about a “divine gift” or a “miracle.”

Naturally, believers treat agnostics better than atheists, due to the fact that any agnostic has the opportunity to find his own path and join a religion. An undoubted advantage is also at least the theoretical possibility of the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence.

Who can consider themselves an agnostic?

Modern society can rightfully consider agnosticism “convenient.” Are you able within yourself to put on the same level the existence of the soul as a whole as a concept, God, forest nymphs, Orpheus and Buddha? An agnostic can. For him, any belief is interesting, and he can treat with reverence both the Gospel, the Holy Scripture, and find something worthwhile in the laws of Sharia.

A little more about the essence of the concept

In order to fully understand the meaning of this term, let us turn again to the etymology. Already at the birth of agnosticism, a morpheme of negation was added to the root borrowed from the Greek language. So from gnosis came agnostos, which translated means “inaccessible to knowledge.”

What is hidden behind the word “agnostic”? Its definition was finally formulated relatively recently - in 1869, but this does not at all indicate the absence of agnosticism as a phenomenon and point of view until then. Even during Antiquity, this position took place, and over time it strengthened, developed and improved. In particular, in the philosophy of Protagoras, in ancient skepticism and among the sophists, the key ideas of this direction were clearly visible.

To a greater extent, views of this kind were characteristic of idealist philosophers.

Scientific agnosticism

We have already mentioned above that the term “agnosticism” was proposed in 1869 by the scientist Thomas Henry Huxley (1825-1895), who, by the way, was not even a philosopher, but became famous for his scientific works in the field of zoology and comparative anatomy.

Moreover, this term was born in response to the question whether a scientist considers himself an atheist or a believer. Huxley considered himself a free-thinking person and stated that, we quote: “a person should not think that he knows something that he has no scientific basis for knowing.”

The term "agnostic" is a symbiosis of the ancient Greek α (alpha), which means "without", and γνῶσις (gnosis), which means "knowledge". So briefly, in one word, the essence of an entire direction in philosophy, science and theology was indicated. Elements of agnosticism can be found in the works of a number of scientists who most people do not associate with either philosophy or theology.

Famous agnostic scientists:

- Charles Darwin.

- Albert Einstein.

- Neil deGrasse Tyson.

Charles Darwin and Albert Einstein were classified as agnostics by biographers who studied their lives and views, but American astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson classified himself as a follower of this trend after he was accused of atheism.

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein, in addition to physics, was keenly interested in the philosophy of science. He wrote that the world around us is a huge eternal mystery, only partially accessible to our perception and our mind. However, the fact that the surrounding reality cannot be completely ordered by reason is the great miracle of science.

This understanding of the relativity of human knowledge probably made it possible for Einstein to create the theory of relativity. For a great scientist, what could not be completely ordered by reason was not at all an obstacle to scientific research, but a challenge that had to be accepted.

Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin did not hide the fact that his attitude towards religion and knowledge changed throughout his life. He is credited with the phrase that, we quote: “There is nothing more remarkable than the spread of religious unbelief, or rationalism, during the second half of my life.”

At the same time, Darwin himself emphasized that he was not an atheist in the generally accepted sense, i.e. does not deny the possibility of the existence of God. And he believed that the theory of evolution he developed did not in any way contradict his views on religion and the process of cognition. Moreover, Darwin wrote that “the more we understand the laws of nature, the more incredible miracles become to us.”

Neil deGrasse Tyson

Neil deGrasse Tyson became famous for his initiative to change the classification of planets and move away from simple counting and assigning a serial number. In his opinion, planets should be grouped according to their common characteristics: terrestrial planets, gas giants, etc. In a sense, Tyson became an “atheist” even in the world of science, having swung at the foundations familiar to everyone.

It is not surprising that he was often accused of almost all mortal sins, including atheism. To this Tyson replied that he is a scientist and thinks with his own head, so the definition of “agnostic” is more suitable for him, i.e. a person who, we quote: “is ready to accept evidence if it exists.” Apparently, this also applies to evidence of the existence of God, if any is found.

Now let’s summarize the main postulates of agnosticism:

- Any knowledge is relative.

- Any statement may turn out to be true.

- Any statement may turn out to be false.

So what is agnosticism anyway - the path to freedom of knowledge or a relic of the past? Rather, this is the path to freedom of knowledge and new discoveries, if we accept the relativity of human knowledge not as a limiter, but as a challenge for further movement forward. This is also an opportunity to question the practical sufficiency and finality of any of the previously made discoveries, which, in turn, opens the way to new scientific achievements.

Well, now you can test yourself and find out how well you understand agnosticism, based on the material in the article:

By the way, if you are interested in the topic of cognition, we invite you to our program “Cognitive Science. Development of Thinking”, where you will master about two dozen thinking techniques.

We wish you new knowledge and impressive discoveries!

We also recommend reading:

- Storytelling

- Materialism and idealism in philosophy

- Philosophy of conventionalism

- Paul Feyerabend's Epistemological Anarchism: Promise or Delusion?

- Philosophical foundations of the linguistic concept of Wilhelm von Humboldt

- Theory of knowledge

- The emergence of positivism

- Machism: Ernst Mach's contribution to the development of the philosophy of positivism

- Neopositivism and the principle of verification

- Empiricism in modern philosophy in simple words

- Why understand philosophy?

Key words:1Cognitive science

Attitude to religions

Agnosticism does not mean denying the existence of a Higher Power, it only asserts the impossibility of knowing whether God really exists or not, and explains the unreality of obtaining reliable and accurate information, true knowledge on this fact.

When a person does not have enough evidence of the existence of God, he makes attempts to find them, puts forward hypotheses, conducts research, refuting or proving them, but ultimately concludes that it is still impossible to prove the existence or non-existence of Higher powers. The same applies to various cognitive and philosophical reasoning.

Important!

An agnostic does not profess “agnosticism,” because such a religion simply does not exist. Agnosticism is a philosophical direction, doctrine, theory of knowledge.

Agnosticism leads to the fact that it itself is unknowable; it is just a means of replenishing and expanding knowledge, forming thoughts, and gaining experience.

Notable agnostics include:

I. Kant, B. Russell, F. Hayek, C. Darwin, A. Einstein, E. Gaidar and others.

Skepticism and agnosticism. general characteristics

A movement that denies the existence of truth is called “skepticism.” It was the skeptics who made the declaration “There is no Truth” the main thesis of their doctrine. Which, of course, was not at all accidental. The skeptics arrived at their thesis - strange as it may seem at first glance - in an obvious way, that is, by logically developing certain positive statements. Zeno's famous aporia proved that space is both discontinuous and continuous, that is, it can be neither one nor the other. Space, understood as discontinuous, makes this idea absurd. Even as a continuous space. Therefore, it had to combine contradictory properties. And this conclusion seemed logically infallible. It seemed that she was revealing the boundaries of logic, the fallacy of its rule, according to which phenomena are always one, always identical to themselves. That is, that truth is inconsistent. Here it seemed to the researchers that both the direct and the reverse statements were true. What could the researchers do? Just fold your hands and admit: “There is no truth.” After all, truth is a certain proposition. There is no truth where a diametrically opposed judgment is recognized along with the judgment as equally true. It so happened that the ancient skeptics, faced with some features of the movement, with its obvious contradictions, gnashed their wisdom teeth.

Should you become an agnostic?

Today, the number of agnostics and atheists is constantly growing in the world. This is primarily due to the progressive development of society and science. And also with the fact that more and more states are becoming secular (non-religious). Therefore, the question of “Should you become an agnostic” rests solely on you and your views. You must decide for yourself which views and positions are more true for you.

How to become agnostic

Since agnosticism is not a religion, the procedure for becoming a representative of this movement is quite simple. Awareness of the reality of “I am an agnostic” requires going through a certain process of familiarization with the relevant literature. Let's look at this process:

- Study the literature on agnosticism;

- Decide whether such positions are suitable for you personally;

- If you are a representative of any religion, then you need to renounce it. Since faith presupposes absolute faith in the presence of higher powers. There should be no hesitation here;

- Just start sticking to agnostic principles.

You cannot remain, for example, a Jew if you are an agnostic

How to stop being agnostic

The procedure is as easy as becoming an agnostic. Just stop classifying yourself as an agnostic. There are no special ways out of this “faith.” You, like all people, are constantly developing, and accordingly, your worldview and outlook on life may change with age.