Associative learning.

Also on the topic:

HUMAN BRAIN

From the time of Aristotle to the present day, the basic principle of learning—association by contiguity—has been formulated in a similar way. When two events are repeated with a short interval (temporal contiguity), they are associated with each other in such a way that the occurrence of one recalls the other. Russian physiologist Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (1849–1936) was the first to study the properties of associative learning in laboratory conditions. Pavlov discovered that although the sound of the bell initially had no effect on the dog's behavior, if it rang regularly at the time of feeding, after a while the dog developed a conditioned reflex: the bell itself began to cause it to salivate. Pavlov measured the degree of learning by the amount of saliva released during a call that was not accompanied by feeding ( see

. CONDITIONED REFLEX). The method of developing conditioned reflexes is based on the use of an already existing connection between a specific form of behavior (salivation) and a certain event (the appearance of food) that causes this form of behavior. When a conditioned reflex is formed, a neutral event (bell) is included in this chain, which is associated with a “natural” event (the appearance of food) to such an extent that it performs its function.

Psychologists have studied associative learning in detail using the so-called method. paired associations: verbal units (words or syllables) are learned in pairs; Subsequent presentation of one member of the pair triggers recall of the other. This type of learning takes place during the acquisition of a foreign language: an unfamiliar word forms a pair with its equivalent in the native language, and this pair is memorized until, when a foreign word is presented, the meaning conveyed by the word in the native language is perceived.

3.2.4. Types of intellectual learning

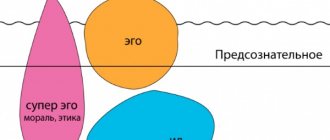

- More complex forms of learning relate to intellectual learning, which, like associative learning, can be divided into reflexive and cognitive (see Fig. 8).

- Reflexive intellectual learning is divided into relational learning, transfer learning and sign learning.

- The essence of teaching relationships is to isolate and reflect in the psyche the relationships of elements in a situation, separating them from the absolute properties of these elements.

Learning through transfer consists of “the successful use, in relation to a new situation, of those skills and innate forms of behavior that the animal already possesses” (Ibid. p. 59). This type of learning is based on the ability to identify relationships and actions.

- Sign learning is associated with the development of such forms of behavior in which “the animal reacts to an object as a sign, i.e. responds not to the properties of the object itself, but to what this object signifies” (Ibid. p. 62).

- Intelligent Cognitive Training is divided into teaching concepts, teaching thinking and teaching skills.

- Learning concepts consists of mastering concepts that reflect the essential relations of reality and are enshrined in words and combinations of words. Through mastery of concepts, a person assimilates the socio-historical experience of previous generations.

- Teaching thinking consists in “forming in students mental actions and their systems that reflect the basic operations with the help of which the most important relations of reality are learned” (Ibid. p. 77). Learning to think is a prerequisite for learning concepts.

- Teaching skills is about developing in students ways to regulate their actions and behavior in accordance with the goal and situation.

In animals, intellectual learning is presented in its simplest forms; in humans, it is the main form of learning and occurs at the cognitive level.

The considered classification provides a fairly complete description of the main types of learning. However, the following comments are valid. Firstly, it is necessary to clarify the content of teaching thinking and define its essence as the student’s mastery of the operations of analysis and synthesis aimed at reflecting being “in its connections and relationships, in its diverse mediations” (Rubinshtein S.L., 1946. P. 340) . Secondly, it should be noted that with intellectual learning we are dealing with the formation of connections, but “these are essential necessary connections based on real dependencies, and not random connections based on contiguity in a particular situation” (Ibid. S. 341).

Instrumental learning.

Also on topic:

REFLEX

The second type of learning, also related to the basic ones, is carried out by trial and error. It was first systematically studied by the American scientist E. Thorndike (1874–1949), one of the founders of educational psychology. Thorndike placed the cat in a box from which it could only get out by pulling a cord hanging from the lid. After a series of random movements, the cat would eventually pull the cord, usually completely by accident. However, when she was put back in the box, she spent less time pulling the cord again, and when the situation repeated, she was freed from the box instantly. Learning was measured in the seconds it took for the cat to perform the correct action. Another example of instrumental learning is the method proposed by the American psychologist B. Skinner (1904–1990). The Skinner Box is a tight cage with a lever in one of the walls; the goal of the experiment is to teach an animal, usually a rat or pigeon, to press this lever. Before training begins, the animal is deprived of food, and the lever is connected to the mechanism for feeding food into the cage. Although at first the animal does not pay attention to the lever, sooner or later it presses it and receives food. Over time, the interval between pressing the lever decreases: the animal learns to use the relationship between the desired response and feeding.

Sometimes learning a particular behavior is so long or difficult that the animal could never have acquired it by chance. Then the method of “successive approximations” is used. Without waiting for the entire required sequence of actions to be completed, the trainer provides a reward for something similar to the desired behavioral act. For example, if a dog needs to be taught to roll, he is first given a treat simply for lying down on command. After the first part has been mastered, the dog receives reinforcement only when it accidentally performs the desired movement: for example, after lying down, it rolls onto its side. Step by step, the trainer achieves closer and closer compliance with the desired behavior, according to the principle of the children's game “cold - warmer - hot”. In general, instrumental learning is very similar to this game, but the role of the hidden object is played by a specific behavior, and the role of the word “hot” is reinforcement.

Progressive approaches to desired behavior are also used in the treatment of severe forms of schizophrenia, when the only goal is to encourage the patient to move and talk instead of withdrawing and remaining silent. As always with instrumental learning, for the method to be successful it is necessary to find something that the patient wants (for example, sweets, chewing gum or interesting photographs). Once a response has been detected, it is necessary to determine which aspects of the behavior are most desirable and make them a condition for receiving a reward. Let us note that punishment also belongs to the methods of instrumental learning, but here the dependence arises between undesirable behavior and unpleasant influence.

See also

- learning in animals, communication in animals,

- teaching human behavior in an organization,

- learning process in comparative psychology,

- learning,

- problem of instinct, problem of learning,

- knowledge, knowledge acquisition,

- knowledge, information,

- the role of cognitive processes in the formation of skills, the formation of skills,

- psychological processes, teaching,

Unfortunately, it is not easy to provide all the knowledge about learning in one article. But I tried. If you show interest in revealing the details, I will definitely write a sequel! I hope that now you understand what learning is, teaching and why all this is needed, and if you don’t understand, or if you have any comments, then don’t hesitate to write or ask in the comments, I will be happy to answer. In order to gain a deeper understanding, I strongly recommend that you study all the information from the Educational Psychology category.

Sequential learning.

Some types of learning require the performance of separate behavioral acts, each of which is easily mastered individually, but then they are combined into a certain sequence. Research on one type of sequential learning, the so-called. serial verbal learning were started by the German philosopher and psychologist G. Ebbinghaus (1850–1909). Ebbinghaus's experiments involved memorizing lists of words or syllables in a specific order and demonstrated for the first time several well-known laws, in particular the law governing the ability to remember elements of a sequence. This law of “place in a series” states that in any sequence the easiest part to remember is the beginning, then the end, and the most difficult part is the part immediately following the middle. The effect of place in a series appears when performing any task of this kind - from memorizing a telephone number to memorizing a poem.

Mastery of a skill is another type of sequential learning, which differs from verbal learning in that a sequence of motor reactions, rather than verbal ones, is learned. Whatever the area of the skill - sports, playing a musical instrument, or tying shoelaces - mastering it almost always involves three stages: 1) instruction, the purpose of which is to determine the task facing the performer and give recommendations on how to perform it; 2) training, in which the required actions are performed under the control of consciousness, at first slowly and with errors, then faster and more correctly; 3) the automatic stage, when behavioral acts proceed smoothly and require less and less conscious control (examples of an automatic skill are tying shoelaces, changing gears in a car, dribbling the ball by an experienced basketball player).

Secondary reinforcement.

During associative learning, some signals that initially had no value or did not indicate danger are associated in the mind with events that have value or are associated with danger. If this happens, signals or events that were previously neutral in nature begin to act as rewards or punishments; This process is called secondary reinforcement. A classic example of secondary reinforcement is money. Animals in a Skinner box are ready to press a lever to obtain special tokens that can be exchanged for food, or to cause the bell to ring, with the sound of which they are accustomed to identify the appearance of food. Avoidance learning illustrates a variant of secondary reinforcement through punishment. The animal performs certain actions when a signal appears, which, although not itself unpleasant, constantly accompanies some unpleasant event. For example, a dog that is often beaten cowers and runs away when its owner raises his hand, although there is nothing dangerous in the raised hand itself. When positive and negative secondary reinforcement is used to control behavior, there is no need for frequent actual rewards or punishments. Thus, when animals are trained using the successive approach method, the reinforcement for each attempt is usually only the clicking sound that previously regularly accompanied the appearance of food.

Approaches to Understanding Learning

There are several approaches to understanding the nature of the emergence and mechanisms of development of learning. Each point of view proposed by scientists has its own characteristics and must be considered in this context.

Conditionally, positions can be divided into several groups:

- theories of behaviorism - learning is interpreted as a random phenomenon caused by a certain set of circumstances, requiring an immediate response;

- theories of Gestalt psychology and neobehaviorism - the entire process of interaction begins with the emergence of spontaneous interest and ends with its complete satisfaction;

- theories that recognize learning as a cognitive activity, during which theoretical knowledge and practical skills are comprehensively applied.

R.G. Averkin highlighted some provisions, combining similar ideas from different approaches to understanding the essence of the phenomenon:

- Learning can be expressed in both gradual and abrupt changes in behavior.

- Changes in behavior are not due to the maturation of the organism, although development is unnatural without learning.

- Changes in behavior due to fatigue or the influence of provoking substances cannot be called learning.

- Regular exercise invariably improves learning.

- The ability to learn is available to varying degrees only at certain species levels.

Reward or punishment.

One of the problems of learning is not only to achieve new, desirable behavior, but also to get rid of unwanted manifestations. The main purpose of punishment is to eliminate existing behavior, not to replace it with new behavior. Often, for example, when raising children or teaching them, the question arises what is better: to punish for an offense or to wait for the desired behavior and reward the child. The greatest results are achieved when punishment accompanies old behavior and reward accompanies new behavior. Although this is just a general rule that cannot be applied in all situations, it highlights an important principle: one should pay attention not only to the behavior itself - undesirable, eliminated by punishment, and desirable, encouraged by reward - but also to the availability of alternatives to it. type of behavior. If you need to wean a child from pulling a cat's tail, then, according to this principle, it is necessary not only to punish the child, but also to offer him another activity (for example, playing with a toy car) and reward him for switching. If a person masters working with any mechanism, the instructor should not just wait patiently for him to do everything correctly, but show him his mistakes.

3.2.2. Levels of learning

- Each type of learning can be divided into two subtypes: reflexive;

- cognitive.

When learning is expressed in the assimilation of certain stimuli and reactions, it is classified as reflex; when mastering certain knowledge and certain actions, they talk about cognitive learning. Learning occurs constantly, in a variety of situations and activities. Depending on the way in which learning is achieved, it is divided into two different levels - reflexive and cognitive. At the reflex level, the learning process is unconscious, automatic. In this way, the child learns, for example, to distinguish colors, the sound of speech, to walk, to reach and move objects. The reflex level of learning is also preserved in an adult, when he unintentionally remembers the distinctive features of objects and learns new types of movements. But for humans, much more characteristic is the higher, cognitive level of learning, which is built on the assimilation of new knowledge and new ways of acting through conscious observation, experimentation, comprehension and reasoning, exercise and self-control. It is the presence of a cognitive level that distinguishes human learning from animal learning. However, not only the reflexive, but also the cognitive level of learning does not turn into learning if it is controlled by any goal other than the goal of mastering certain knowledge and actions. As studies by a number of psychologists have shown, in some cases spontaneous, unintentional learning can be very effective. For example, a child remembers better what is related to his active activity and is necessary for its implementation than what he memorizes specifically. However, in general, the advantage is undeniably on the side of conscious, purposeful learning, since only it can provide systematized and deep knowledge.

Partial reinforcement.

Instrumental learning using rewards—for example, training a rat in a Skinner box to press a lever for food or praising a child when he says “thank you” and “please”—involves several types of relationships between behavior and reinforcement. The most common type of addiction is constant reinforcement, in which a reward is given for each correct response. Another option is partial reinforcement, which offers reinforcement only for some correct responses, say every third time the desired behavior occurs, or every tenth time, or the first time it occurs every hour or every day. The effects of partial reinforcement are important and of great interest. With partial reinforcement, it takes longer to learn the desired behavior, but the results are much more durable. The persistence of the effect is especially noticeable when the reinforcement is stopped; This procedure is called "extinction". Behavior learned with partial reinforcement persists for a long time, while behavior mastered with constant reinforcement quickly ceases.

TRANSFER AND INTERFERENCE

Learning a particular type of behavior rarely occurs in isolation. More often, there are similarities between the situations in which different types of behavior are learned, or similarities between the types of behavior themselves. When, for example, two successive learning tasks are similar, completing the first one makes it easier to complete the second; this effect is called “carryover.” Positive transfer occurs when mastering the first skill helps in mastering the second; for example, having learned to play tennis, a person will more easily learn to play badminton, and a child who can write on a blackboard will more easily master writing with a pen on paper. Negative transference occurs in opposite situations, i.e. when mastering the first task interferes with learning to perform the second: for example, having incorrectly remembered the name of a new acquaintance, it is more difficult to learn the correct name; The ability to change gears in a car of one brand can make it difficult to use a car of another brand, where all the levers are located differently. The general principle is as follows: positive transfer is possible between two activities if the second of them requires the same behavior as the first, but in a different situation; Negative transfer occurs when learning a new way of behavior to replace the old one in the same situation.

Negative transfer is of particular interest. When studying it experimentally, “extinction” is used, i.e. procedure when the reinforcement stops. Although such experiments are usually carried out to monitor the disappearance of previously reinforced behavior, they lead to the conclusion that the latter is always replaced by new behavior - even if only inaction. The so-called verbal interference, the essence of which is that new verbal material is remembered worse due to the overlap of other, already known material of the same kind; in such cases, the task of associative learning is to form a new association to a word or object that is already associated with something (for example, when the subject is required to remember that in French his pet is called chien, not dog). Finally, in psychotherapy there is a method of counterconditioning, according to which patients suffering from obsessive fear (phobia) are taught to relax when they see an object that causes fear or something that symbolizes it. Thus, a patient who is afraid of snakes is first taught the method of deep relaxation, and then he is gradually taught to think about snakes during relaxation, replacing the previously existing fear with calm behavior. In all such situations, when two interfering reactions arise, the severity of conflicting types of behavior clearly depends on the time that has elapsed since their development. If success is assessed immediately after a new task has been mastered—either in a series of experiments without reward, or by repeatedly calling the dog the word chien, or by repeatedly pairing relaxation with the idea of a snake—the second type of behavior appears to be dominant. However, if there is a break in training, the first type of behavior reappears. For example, if a person, after diligently practicing, finally learned to change gears in a new car, where the handles are located differently than in the old one, then a week-long break will lead to the restoration of the previous habit and errors in the application of the new skill. Periodic training of a new type of behavior time after time reduces the likelihood of relapse, but since previous actions are never completely eradicated, some experts are inclined to believe that the original learning is never completely erased, and new reactions only dominate over old ones.

Types, conditions and mechanisms of learning. factors determining its success

Types, conditions and mechanisms of learning. factors determining its success

There are several concepts related to a person’s acquisition of life experience in the form of knowledge, skills and abilities.

This is educational activity, teaching, teaching and teaching. Educational activity is a process as a result of which a person acquires new or changes his existing knowledge, skills and abilities, improves and develops his abilities. Such activity allows him to adapt to the world around him, navigate it, and more successfully and more fully satisfy his basic needs, including the needs of intellectual growth and personal development. The second of these concepts - learning - presupposes the joint educational activity of a student and a teacher, characterizes the process of transferring knowledge, skills, and, more broadly, life experience from teacher to student. When they talk about teaching, they focus on what the teacher does, on his specific functions in the learning process. The third concept - teaching - also refers to educational activity, but when it is used in science, attention is drawn mainly to what is the responsibility of the student in the educational activity. We are talking about educational activities undertaken by the student aimed at developing abilities and acquiring the necessary knowledge, skills and abilities. All three concepts considered relate to the content of the educational process. When they want to emphasize the result of teaching, they use the concept of learning. It characterizes the fact that a person acquires new psychological qualities and properties in educational activities. Etymologically, this concept comes from the word “learn” and includes everything that an individual can actually learn as a result of training and teaching. Let us note that teaching and learning, educational activities in general, may not have a visible result in the form of learning. This is another basis for separating the concepts under discussion and their parallel use.

Characterizing educational activity from different angles as a process of educational and cognitive interaction between a teacher and students, we will use all four concepts, preferring one to the other depending on which specific aspect of the interaction between teacher and students receives primary attention. Let's start with the question of learning.

First, let us note: not everything related to development can be called learning. For example, it does not include the processes and results that characterize the biological maturation of the organism; they unfold and proceed according to biological, in particular genetic, laws. Although maturation processes are also associated with the acquisition of new things by the body and changes in existing experience, although they can also contribute to better adaptation of the organism to environmental conditions, these processes nevertheless cannot be called learning. They depend little or little on teaching and learning. For example, the external anatomical and physiological similarity of a child and parents, the ability to grasp objects with hands, follow them, and a number of others arise mainly according to the laws of maturation. It, in turn, can be defined as a biologically determined process of changing the body, its functions, including some psychological and behavioral characteristics, which were probably initially inherent in the genotype.

Any process called learning is not, however, completely independent of maturation. This is recognized by all scientists, and the only question is what is the extent of this dependence and to what extent development is determined by maturation. Learning is almost always based on a certain level of biological maturity of the organism and cannot take place without it. It is hardly possible, for example, to teach a child to speak until the time when the organic structures necessary for this have matured:

the vocal apparatus, the corresponding parts of the brain responsible for speech, and more. Learning, in addition, depends on the maturation of the organism according to the nature of the process: it can be accelerated or inhibited according to the acceleration or deceleration of the maturation of the organism. The importance of maturation for learning was well emphasized by P. Teilhard de Chardin, noting: “Without a long period of maturation, no profound change in nature can occur.”

There may also be an inverse relationship between these processes; teaching and learning to a certain extent influence the maturation of the organism, so that in reality they are mutually determined. True - and this should be definitely noted - this dependence is not absolutely two-sided, i.e., the same on both sides. Learning depends to a much greater extent on maturation than, conversely, maturation on learning, since the possibilities of external influence on genotypically determined processes and structures in the body are very limited.

A person has several types of learning. The first and simplest of them unites humans with all other living beings that have a developed central nervous system. This is learning through the mechanism of imprinting, i.e. fast, automatic, almost instantaneous compared to the long process of learning to adapt the organism to the specific conditions of its life using forms of behavior that are practically ready from birth. For example, it is enough for a mother duck to appear in the field of view of a newborn duckling and begin to move in a certain direction, and, standing on its own paws, the chick begins to automatically follow her everywhere. This happens, as K. Lorenz showed, even when the field of view of a newborn chick is not a mother duck, but some other moving object, for example a person. Another example: it is enough to touch the inner surface of a newborn’s palm with any hard object, and his fingers automatically clench. As soon as a newborn touches the mother's breast, his innate sucking reflex is immediately triggered. Through the described mechanism of imprinting, numerous innate instincts are formed, including motor, sensory and others. According to tradition, which has developed since the time of I.P. Pavlov, such forms of behavior are called unconditioned reflexes, although the word “instinct” is more suitable for their name. Such forms of behavior are usually genotypically programmed and are difficult to change. Nevertheless, elementary learning, at least in the form of a suitable “trigger” signal, is also necessary for the activation of instincts. In addition, it has been shown that many instinctive forms of behavior are themselves quite plastic.

The second type of learning is conditioned reflex learning. His research began with the work of I. P. Pavlov. This type of learning involves the emergence of new forms of behavior as conditioned reactions to an initially neutral stimulus, which previously did not cause a specific reaction. Stimuli that are capable of generating a conditioned reflex reaction of the body must be perceived by it. All the basic elements of the future reaction must also already be present in the body. Thanks to conditioned reflex learning, they are connected with each other into a new system that ensures the implementation of a more complex form of behavior than elementary innate reactions.

Conditioned stimuli are usually neutral from the point of view of the process and conditions for satisfying the body's needs, but the body learns to respond to them during life as a result of the systematic association of these stimuli with the satisfaction of corresponding needs. Subsequently, in this process, conditioned stimuli begin to play a signaling, or orienting, role.

Conditioned stimuli can be associated with conditioned reactions in time or space (see the concept of association). For example, a certain, habitual environment in which a baby repeatedly finds himself during feeding can, through a conditioned reflex, begin to evoke in him organic processes and movements associated with eating. A word, as a certain combination of sounds, associated with highlighting in the field of vision or holding an object in the hand, can acquire the ability to automatically evoke in a person’s mind an image of this object or movements aimed at searching for it.

The third type of learning is operant learning. With this type of learning, knowledge, skills and abilities are acquired through the so-called trial and error method. It is as follows. The task or situation faced by an individual gives rise to a complex of various reactions: instinctive, unconditional, conditional. The body consistently tries each of them in practice to solve a problem and automatically evaluates the result achieved. That one of the reactions or that random combination of them that leads to the best result, that is, ensures the optimal adaptation of the body to the situation that has arisen, stands out among the rest and is consolidated in experience. This is learning by trial and error. All the types of learning described are found in both humans and animals and represent the main ways in which various living beings acquire life experience. But man also has special, higher methods of learning, rarely or almost never found in other living beings. This is, firstly, learning through direct observation of the behavior of other people, as a result of which a person immediately adopts and assimilates the observed forms of behavior. This type of learning is called vicarious and is represented in humans in its most developed form. In terms of its mode of functioning and results, it resembles imprinting, but only in the sphere of a person’s acquisition of social skills.

Secondly, this is verbal learning, that is, a person’s acquisition of new experience through language. Thanks to him, a person has the opportunity to transfer to other people who speak speech, and to obtain the necessary abilities, knowledge, skills and abilities, describing them verbally in sufficient detail and understandably for the learner. Speaking more broadly, in this case we mean learning carried out in symbolic form through diverse sign systems, among which language acts as one of such systems. These also include symbolism used in mathematics, physics, and many other sciences, as well as graphic symbolism used in technology and art, in geography, geology and other fields of knowledge.

Vicarious learning is especially significant for a person in the early stages of ontogenesis, when, not yet mastering the symbolic function, the child acquires rich and varied human experience, learning from visual examples through observation and imitation. Symbolic, or verbal, learning becomes the main way of acquiring experience, starting from the moment of mastering speech and especially when studying at school. The assimilation of language and other systems of symbols, the acquisition of the ability to operate with them frees a person from direct sensory attachment to objects, makes his learning (training, teaching, organization of educational activities) possible in an abstract, abstract form. Here, the prerequisite and basis for effective learning are the most perfect higher mental functions of a person: his consciousness, thinking and speech.

Let us note two particular but important additional differences that exist between learning, teaching and teaching. Teaching differs from teaching, in addition to what was said above, also in that it is usually an organized process, systematically and consciously controlled, while learning can occur spontaneously. Teaching, as an aspect of educational activity related to the student’s work, can also act as an organized or unorganized process. In the first case, teaching is an aspect of learning, interpreted in the broad sense of the word, and in the second, it is the result of what is called socialization. Learning can be a by-product of any activity, while the concepts of teaching and learning are usually associated with special educational activities.

If the main motive for activity is cognitive interest or the psychological development of the individual, then we speak of educational activity. If the motive is to satisfy some other needs of the individual, then the concept of “learning” is often used. An example of such incidental learning could be the involuntary memorization of information or actions related to any activity that does not directly pursue educational goals.

Teaching and learning are almost always conscious processes, while learning can also occur at an unconscious level. A person who has learned something may not be aware that this learning actually happened. For example, people often discover in themselves habits, statements, actions and movements characteristic of other people, and often completely unexpectedly for themselves, since, while observing other people, they did not consciously set themselves the goal of remembering, learning and appropriating the observed forms of behavior .

The difference between teaching, teaching and learning is also seen in the fact that readiness for these types of information appropriation in children is detected at different age periods. The child is practically ready for elementary types of learning - imprinting, conditioned reflex, operant - from the first days and months of life, that is, almost immediately after birth. Learning ability as the ability to consciously, purposefully acquire knowledge, skills and abilities appears in him around 4-5 years, and full readiness for independent learning arises only in the first grades of school, i.e. at the age of about 7-8 years.

The learning process, as an activity, is realized through the following educational and intellectual mechanisms:

1. Formation of associations. This mechanism underlies the establishment of temporary connections between individual knowledge or

parts of experience.

2. Imitation. Acts as the basis for the formation of mainly skills and abilities.

3. Distinction and generalization. Associated primarily with the formation of concepts.

4. Insight (guess). It represents a person’s direct viewing of some new information, something unknown in what is already known, familiar from past experience. Insight is the cognitive basis for the development of a child's intelligence.

5. Creativity. It serves as the basis for the creation of new knowledge, subjects, skills and abilities that are not presented in the form of ready-to-learn samples through imitation.

The task of improving learning comes down to using all the described mechanisms in it. The success of learning depends on many factors, and among them psychological factors occupy an important place. These are the motivation of learning activities, the arbitrariness of cognitive processes of perception, attention, imagination, memory, thinking and speech, which we have already discussed in the course of general fundamentals of psychology, the presence of the necessary strong-willed and a number of other personality qualities in the student: perseverance, determination, responsibility, discipline, consciousness, accuracy and others. Psychological factors for the success of educational activities also include the ability to interact with people in joint activities with them, primarily with teachers and study group mates, intellectual development and the formation of educational activities as teachings. All of these factors apply not only to the student, but also to the teacher, but to the latter - in their specific refraction associated with teaching other people. An important role in the process of acquiring knowledge is the learning mindset, i.e. the teacher’s setting and the student’s acceptance of a learning task, the meaning of which for the teacher is to teach, and for the student to learn something.

All considered learning factors relate to the personality and psychological characteristics of people included in the educational process. But, besides them, there are also the means and content of teaching, the educational material that the teacher and students use. It must also meet certain requirements. The most important of them is accessibility and a sufficient level of complexity. Accessibility ensures that the student masters this material, and sufficient complexity ensures the student’s psychological development. From a psychological point of view, the optimal complexity from a psychological point of view is considered to be educational material that is at a fairly high, but still quite accessible level of difficulty. By learning from such material, children not only experience the greatest personal satisfaction with success, but also develop best intellectually.

A subjectively important point related to the student’s assessment of the degree of difficulty of the material being learned is interest in it and the connection of this material with the needs of the student, with his experience, skills and abilities. Material that is interesting, familiar, and personally relevant is typically perceived by students as less difficult than material that has the opposite characteristics.

An important factor in the success of teaching and learning is a well-thought-out system of rewarding students for success and punishment for failure in educational activities. Rewards should correspond to real success and reflect not so much the student’s abilities as the efforts he makes. Punishments should play a stimulating role, i.e., affect and activate important motives of educational activity aimed at achieving success rather than avoiding failure.

Encoding information in memory.

Many types of learning involve three essential elements: sound, meaning and sight. For example, it is necessary to form an association between the words “dog” and “table”. Learning by encoding sounds requires repeating those words over and over again, listening to how they sound together, and remembering how they feel when they are repeated. This acoustic method, called rote memorization, is sometimes necessary, but is significantly inferior in meaning to encoding. Meaningful learning of the association between the words “dog” and “table” involves thinking about a dog, thinking about a table, and making some kind of connection between them, such as the statement that a dog never works at a table. Semantic encoding is the most important factor in successful school education. Long hours of hard work using rote memorization do not produce the same results as those achieved through much fewer sessions that focus on the meaning of the lesson. Sometimes the third method turns out to be the most effective - the method of forming visual images. In the case of “dog” and “table,” the procedure would be to create a realistic mental image in which both the dog and the table play important roles, such as an image of an antique desk on which stands a paperweight with a handle in the shape of a hunting dog. The more vivid the image is, the easier it is to subsequently remember the connection between these two objects. Of course, in some cases, especially when it comes to abstract concepts like "misfortune" and "energy", there is no simple way of visual representation and you have to rely only on semantic encoding. Thus, effective learning is not only achieved through time and effort spent on practice; The nature of the practice itself is also of great importance.

3.1.1. A system of activities as a result of which a person gains experience

There are several concepts related to a person’s acquisition of life experience in the form of knowledge, skills, abilities, abilities. This is teaching, teaching, teaching. The most general concept is learning. Intuitively, each of us has an idea of what learning is. They talk about learning when a person began to know and (or) be able to do something that he did not know and (or) could not do before. This new knowledge, skills and abilities can be a consequence of activities aimed at acquiring them, or act as a side effect of behavior that realizes goals not related to this knowledge and skills. Learning denotes the process and result of the acquisition of individual experience by a biological system (from the simplest to man as the highest form of its organization in the conditions of the Earth). Such familiar and widespread concepts as evolution, development, survival, adaptation, selection, improvement, have some commonality, most fully expressed in the concept of learning, which resides in them either explicitly or by default. The concept of development, or evolution, is impossible without the assumption that all these processes occur due to changes in the behavior of living beings. And at present, the only scientific concept that fully embraces these changes is the concept of learning. Living things learn new behaviors that enable them to survive more effectively. Everything that exists adapts, survives, acquires new properties, and this happens according to the laws of learning. So, survival mainly depends on learning ability. In foreign psychology, the concept of “learning” is often used as an equivalent to “teaching”. In Russian psychology (at least during the Soviet period of its development), it is customary to use it in relation to animals. However, recently a number of scientists (I.A. Zimnyaya, V.N. Druzhinin, Yu.M. Orlov, etc.) have used this term in relation to humans. To better understand the differences between learning, teaching and learning, we will use the classification of activities as a result of which a person gains experience (Gabay T.V., 1995; abstract). All activities in which a person gains experience can be divided into two large groups: activities in which the cognitive effect is a side (additional) product and activities in which the cognitive effect is its direct product (see Fig. 1). Learning includes the acquisition of experience in all types of activities, regardless of its nature. In addition, the acquisition of experience as a by-product, depending on the regularity, in certain types of activity can be stable, more or less constant, or random, episodic. The acquisition of experience as a stable by-product can occur in the process of spontaneous communication, in play (if it is not organized by an adult specifically for the purpose of the child acquiring some type of experience). In all these types of activities (play, work, communication, intentional cognition), experience can also be acquired as an accidental by-product. The second large group of activities in which a person gains experience consists of those types of activities that are consciously or unconsciously carried out for the sake of the experience itself. Let us first consider activities in which the acquisition of experience is carried out without setting a corresponding goal. Among them the following types can be distinguished: didactic games, spontaneous communication and some other activities. All of them are characterized by the fact that, although the subject of acquiring experience does not set himself the goal of mastering this experience, he naturally and consistently receives it at the end of their process. In this case, the cognitive result is the only rational justification for the expenditure of time and effort of the subject. At the same time, the actual motive is shifted to the process of activity: a person communicates with others or plays because he enjoys the very process of communication or play. In addition to didactic play and spontaneous communication, the acquisition of experience as a direct product, but without a conscious goal, is also achieved in free observation, while reading fiction, watching films, performances, etc. Discovery or assimilation become one of the most significant criteria for the classification of types of knowledge. In turn, assimilation also involves two options:

- when the experience is given in ready-made form, but the subject of assimilation must independently prepare all or some of the conditions that ensure the process of assimilation;

- when he performs only the cognitive components of this activity, and the conditions for assimilation are prepared by other people.

The last option is of the greatest interest to us, since it reflects the essential features of a phenomenon that takes place in any human being and consists in the transfer by the older generation to the younger generation of the experience that society has. This type of activity is teaching.

Organization of practice.

When mastering a skill, as in many other situations, it is helpful to take frequent rest breaks rather than practice continuously. The same number of lessons will lead to more effective learning if they are distributed over time, and not concentrated in a single block, as is done with the so-called. massive training. Classes held partly in the morning and partly in the evening provide a greater difference in learning conditions than classes only in the morning or only in the evening. However, part of the learning process is for the learner to recall stored information, and such recall is facilitated by recreating the situation in which something was learned. For example, test results are better if it is conducted not in a special examination class, but in the same room where the training took place. see also

NEUROPSYCHOLOGY; MEMORY; PSYCHOLOGY; HABIT.

3.1.2. The relationship between the concepts of “learning”, “teaching” and “training”

Teaching is defined as a person’s learning as a result of his purposeful, conscious appropriation of his transmitted (translated) sociocultural (socio-historical) experience and the individual experience formed on this basis. Consequently, teaching is considered as a type of learning. Learning in the most common sense of this term means the purposeful, consistent transfer (broadcast) of sociocultural (socio-historical) experience to another person in specially created conditions. In psychological and pedagogical terms, learning is considered as managing the process of accumulating knowledge, forming cognitive structures, as organizing and stimulating the student’s educational and cognitive activity (https://www.pirao.ru/strukt/lab_gr/l-ps-not.html; see Laboratory of psychological foundations of new educational technologies). In addition, the concepts of “learning” and “training” are equally applicable to both humans and animals, in contrast to the concept of “teaching”. In foreign psychology, the concept of “learning” is used as an equivalent to “teaching”. If “learning” and “teaching” denote the process of acquiring individual experience, then the term “learning” describes both the process itself and its result. Scientists interpret the triad of concepts under consideration in different ways. For example, the points of view of A.K. Markova and N.F. Talyzina are as follows (see Fig. 2).

- A.K. Markova: considers learning as the acquisition of individual experience, but first of all pays attention to the automated level of skills;

- interprets teaching from a generally accepted point of view - as a joint activity of teacher and student, ensuring that students acquire knowledge and master the methods of acquiring knowledge;

- learning is represented as the student’s activity in acquiring new knowledge and mastering methods of acquiring knowledge (Markova A.K., 1990; abstract).

N.F. Talyzina adheres to the interpretation of the concept of “learning” that existed in the Soviet period - the application of the concept in question exclusively to animals; She considers teaching only as the activity of a teacher in organizing the pedagogical process, and teaching as the activity of a student included in the educational process (Talyzina N.F., 1998; abstract) (https://www.psy.msu.ru/about/kaf /pedo.html; see Department of Pedagogy and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Moscow State University). Thus, the psychological concepts of “learning”, “training”, “teaching” cover a wide range of phenomena related to the acquisition of experience, knowledge, skills, abilities in the process of active interaction of the subject with the objective and social world - in behavior, activity, communication. The acquisition of experience, knowledge and skills occurs throughout the life of an individual, although this process occurs most intensively during the period of reaching maturity. Consequently, the learning processes coincide in time with the development, maturation, mastery of the forms of group behavior of the object of learning, and in a person - with socialization, the development of cultural norms and values, and the formation of personality. So, teaching/training/teaching is the process of a subject acquiring new ways of carrying out behavior and activities, their fixation and/or modification. The most general concept denoting the process and result of the acquisition of individual experience by a biological system (from the simplest to man as the highest form of its organization in the conditions of the Earth) is “learning”. Teaching a person as a result of his purposeful, conscious appropriation of the socio-historical experience transmitted to him and the individual experience formed on this basis is defined as teaching.