Updated July 19, 2021 266 Author: Dmitry Petrov

Hello, dear readers of the KtoNaNovenkogo.ru blog. I am, I am here, I am alive. How do I understand this? Through the reflection of reality by my senses.

For example, right now there is a sound of children’s laughter outside the window. I hear it with my ears. A bright light “hits” my eyes - my eyes see it. Covered with a blanket, I feel warm.

Every sentence talks about sensations - this is what helps us feel here and now.

What is the feeling

Wikipedia says: “ Sensation is a mental process , which is a mental reflection of individual properties and states of the external environment by the subject of internal or external stimuli and stimuli received in the form of signals through the sensory system, with the participation of the nervous system as a whole.”

To put it very simply, sensation is what I feel inside and on the surface of my body in response to some influence.

The following words are most often used as synonyms for “sensation”:

- feeling;

- feeling;

- impression;

- experience from what was seen, heard, experienced, etc.;

- consciousness;

- understanding;

- image.

In psychology, sensation is a process through which we become aware of the different properties of objects in reality. At one moment in time, it is possible to experience only one sensation.

For example, I'll take a cup of hot coffee. I can feel the warmth coming from her, her weight, color, shape, but in turn.

A variety of sensations give a person the opportunity to become aware of himself – his desires and needs (physical and emotional). For example:

- a rumbling stomach tells you that it’s time to eat;

- tension in the jaw, arms and stomach in contact with someone can indicate irritation and even anger, which signals that this someone is somehow violating our boundaries;

- the so-called “butterflies in the stomach” and fluttering in the chest next to a specific individual of the opposite sex (but not necessarily the opposite) “say” that we experience a feeling for him called love.

The intensity of the experience of a sensation depends on the threshold of this sensation. The lower threshold is the minimum strength of the stimulus that causes a response. The upper threshold is the maximum value of the stimulus, after which it ceases to be felt. The difference between the thresholds is the corridor in which the analyzers remain susceptible to influence.

- 6.1. Sensations and their anatomical and physiological mechanisms

- 6.2. Types and properties of sensations

- 6.3. Sensitivity and its changes

- 6.4. Properties and types of perception

- 6.5. Phenomena of perception

Topic 6. Cognitive processes. Sensations and perception

6.1. Sensations and their anatomical and physiological mechanisms

Human life requires an active study of the objective laws of the surrounding reality. Understanding the world and building an image of this world are necessary for a full orientation in it, for a person to achieve his own goals. Knowledge of the surrounding world is included in all spheres of human activity and the main forms of its activity.

In cognition it is customary to distinguish two levels: sensory

and

rational

.

The first level includes cognition through the senses. In the process of sensory cognition, a person develops an image, a picture of the surrounding world in its immediate reality and diversity. Sensory cognition is represented by sensations

and

perception

. In rational knowledge, a person goes beyond the limits of sensory perception, reveals the essential properties, connections and relationships between objects of the surrounding world. Rational knowledge of the surrounding world is carried out thanks to thinking, memory and imagination.

Feeling

– this is the process of primary information processing, which is a reflection of the individual properties of objects and phenomena that arises from their direct impact on the senses, as well as a reflection of the internal properties of the body. Sensation performs the function of orienting the subject in individual, most elementary properties of the objective world.

Sensations are the simplest form of mental activity. They arise as a reflex reaction of the nervous system to a particular stimulus. The physiological basis of sensation is a nervous process that occurs when a stimulus acts on an analyzer adequate to it.

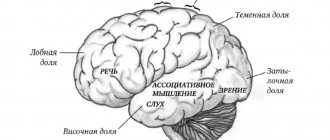

The analyzer consists of three parts: 1) a peripheral section (receptor), which transforms external energy into a nervous process; 2) conducting nerve pathways connecting the peripheral parts of the analyzer with its center: afferent (directed to the center) and efferent (going to the periphery); 3) subcortical and cortical sections of the analyzer, where the processing of nerve impulses coming from peripheral sections occurs.

The cells of the peripheral parts of the analyzer correspond to certain areas of cortical cells. Numerous experiments make it possible to clearly establish the localization in the cortex of certain types of sensitivity. The visual analyzer is represented mainly in the occipital zones of the cortex, the auditory one - in the temporal zones, tactile-motor sensitivity is localized in the posterior central gyrus, etc.

For sensation to occur, the entire analyzer must operate. The impact of an irritant on the receptor causes irritation. The beginning of this irritation is expressed in the transformation of external energy into a nervous process, which is produced by the receptor. From the receptor, this process reaches the cortical part of the analyzer along afferent pathways, as a result of which the body’s response to irritation occurs - a person feels light, sound or other qualities of the stimulus. At the same time, the influence of the external or internal environment on the peripheral part of the analyzer causes a response that is transmitted along the efferent pathways and leads to the pupil dilating or contracting, the gaze being directed to the object, the hand withdrawing from the hot object, etc. The entire described path is called reflex ring

. The interconnection of the elements of the reflex ring creates the basis for the orientation of a complex organism in the surrounding world and ensures the activity of the organism in different conditions of its existence.

6.2. Types and properties of sensations

Since the time of Aristotle, many generations of scientists have focused on only five senses: sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste.

In the 19th century

knowledge about the composition of sensations has expanded dramatically. This occurred as a result of the description and study of their new types - vestibular, vibrational muscular-articular,

or

kinesthetic,

etc. - as well as as a result of clarification of the composition of some complex types of sensations (for example, scientific awareness of the fact that touch is a combination

tactile, temperature, pain

sensations and

kinesthesia,

and in tactile sensations, in turn, one can distinguish the sensations

of touch

and

pressure).

The increase in the number of types of sensations has necessitated their classification.

There are several known attempts to classify sensations according to different bases and principles. The classification proposed by the English physiologist C. Sherrington is considered the most successful and thoughtful .

The basis for this classification was the nature of the reflections and the location of the receptors. C. Sherrington identified three types of receptive fields: interoceptive, proprioceptive and exteroceptive.

Interoceptive

receptors are located in the internal organs and tissues of the body and reflect the state of the internal organs.

These are the most ancient and most elementary sensations, but they are very important as signals about the state of our body. Proprioceptors

are located in muscles, ligaments and tendons. They supply information about the movements and position of our body in space and individual parts of the body relative to each other. These sensations play a critical role in the regulation of movement.

exteroceptive

the receptive field coincides with the outer surface of the body and is completely open to external influences.

Exteroceptors represent the largest group of sensations. Charles Sherrington divided them into contact

and

distant.

Contact receptors (touch, including tactile, temperature and pain sensations, as well as taste buds) transmit irritation through direct contact with objects affecting them. Distant sensations (smell, hearing, vision) occur when a stimulus acts from a certain distance. In the process of evolution, it is distant exteroceptive sensations that begin to play an increasingly important role in cognition of the surrounding world and in the organization of behavior, since they provide an important advantage, allowing them to receive the necessary information about changes in the environment in advance and respond to them.

From the point of view of modern science, the division of sensations into external (exteroceptors) and internal (interoceptors) proposed by C. Sherrington is not enough. Some types of sensations - for example, temperature and pain, taste and vibration, muscle-articular and static-dynamic receptors - can be considered external-internal

.

Sensations are a form of reflection of adequate stimuli. For example, visual sensations arise when exposed to electromagnetic waves with a length in the range from 380 to 780 millimicrons, auditory sensations - when exposed to mechanical vibrations with a frequency of 16 to 20,000 Hz, volume from 16–18 to 120 decibels, tactile sensations are caused by the action of mechanical stimuli on the surface of the skin, vibrations are generated by the vibration of objects. Other sensations (temperature, olfactory, taste) also have their own specific stimuli. Closely related to the adequacy of the stimulus is the limitation of sensations, due to the structural features of the sense organs. The human ear cannot detect ultrasound, although some animals, such as dolphins, have this ability. Human eyes are sensitive to only a small part of the spectrum. A significant part of physical influences that do not have vital significance are not perceived by us. To perceive radiation and some other influences found on Earth in their pure form and in quantities that threaten human life, we simply do not have sense organs.

The general properties of sensations include their quality, intensity, duration and spatial localization.

Qualities

- these are the specific features of this sensation that distinguish it from other types. For example, auditory sensations differ in timbre, pitch, volume; visual - by saturation and color tone; gustatory - according to modality (taste can be sweet, salty, sour and bitter).

Intensity

sensation is its quantitative characteristic and is determined by the strength of the current stimulus and the functional state of the receptors.

Duration

sensations are its temporary characteristics.

It is largely determined by the functional state of the sense organs, but mainly by the time of action of the stimulus and its intensity. It must be borne in mind that when a stimulus acts on a sense organ, the sensation does not occur immediately, but after some time, which is called latent period

. The latent period for different types of sensations is not the same: for tactile sensations, for example, it is 130 milliseconds, for pain – 370 milliseconds, taste sensations arise 50 milliseconds after applying a chemical irritant to the surface of the tongue. Just as a sensation does not arise simultaneously with the onset of the stimulus, it does not disappear with the cessation of the latter. This inertia of sensations manifests itself in the so-called aftereffect.

Spatial localization

The stimulus also determines the nature of the sensations. Spatial analysis, carried out by distant receptors, provides information about the localization of the stimulus in space. Contact sensations correspond to the part of the body that is affected by the stimulus. At the same time, the localization of pain sensations can be more diffuse and less accurate than tactile ones.

6.3. Sensitivity and its changes

Various sense organs that give us information about the state of the world around us may be more or less sensitive to the phenomena they display, that is, they may reflect these phenomena with greater or less accuracy. The sensitivity of the senses is determined by the minimal stimulus that, under given conditions, is capable of causing sensation.

The minimum strength of the stimulus that causes a barely noticeable sensation is called the lower absolute threshold of sensitivity

.

Stimuli of lesser strength, so-called subthreshold, do not cause sensations. The lower threshold of sensations determines the level of absolute sensitivity

of this analyzer.

There is an inverse relationship between absolute sensitivity and the threshold value: the lower the threshold value, the higher the sensitivity of a given analyzer. This relationship can be expressed by the formula E = 1/P,

where

E

is the sensitivity,

P

is the threshold value.

Analyzers have different sensitivities. Humans have very high sensitivity visual and auditory analyzers. As the experiments of S.I. Vavilova

, the human eye is capable of seeing light when only 2–8 quanta of radiant energy hit its retina. This allows you to see a burning candle on a dark night at a distance of up to 27 km.

The auditory cells of the inner ear detect movements whose amplitude is less than 1% of the diameter of a hydrogen molecule. Thanks to this, we hear the ticking of a clock in complete silence at a distance of up to 6 m. The threshold of one human olfactory cell for the corresponding odorous substances does not exceed 8 molecules. This is enough to smell one drop of perfume in a room of 6 rooms. It takes at least 25,000 times more molecules to produce the sensation of taste than to create the sensation of smell. In this case, the presence of sugar is felt in a solution of one teaspoon per 8 liters of water.

The absolute sensitivity of the analyzer is limited not only by the lower, but also by the upper sensitivity threshold,

i.e., the maximum strength of the stimulus, at which a sensation adequate to the current stimulus still arises. A further increase in the strength of stimuli acting on the receptors causes only painful sensations in them (such an effect is exerted, for example, by super-loud sound and blinding brightness).

The magnitude of absolute thresholds depends on the nature of the activity, age, functional state of the body, strength and duration of irritation.

In addition to the magnitude of the absolute threshold, sensations are characterized by an indicator of the relative, or differential, threshold. The minimum difference between two stimuli that causes a barely noticeable difference in sensation is called the discrimination threshold, difference or differential threshold

. The German physiologist E. Weber, testing a person’s ability to determine the heavier of two objects in the right and left hand, established that differential sensitivity is relative and not absolute. This means that the ratio of the subtle difference to the magnitude of the original stimulus is constant. The greater the intensity of the original stimulus, the more it must be magnified to notice a difference, i.e., the greater the magnitude of the subtle difference.

The differential threshold of sensations for the same organ is a constant value and is expressed by the following formula: dJ/J = C

, where

J

is the initial magnitude of the stimulus,

dJ

is its increase, causing a barely noticeable sensation of a change in the magnitude of the stimulus, and

C

is a constant. The value of the differential threshold for different modalities is not the same: for vision it is approximately 1/100, for hearing – 1/10, for tactile sensations – 1/30. The law embodied in the above formula is called the Bouguer–Weber law. It must be emphasized that this is only valid for mid-ranges.

Based on Weber's experimental data, the German physicist G. Fechner expressed the dependence of the intensity of sensations on the strength of the stimulus with the following formula: E = k*

log

J + C

, where

E is

the magnitude of sensations,

J is

the strength of the stimulus,

k

and

C

are constants. According to the Weber-Fechner law, the magnitude of sensations is directly proportional to the logarithm of the intensity of the stimulus. In other words, the sensation changes much more slowly than the strength of irritation increases. An increase in the strength of stimulation in geometric progression corresponds to an increase in sensation in arithmetic progression.

The sensitivity of analyzers, determined by the magnitude of absolute thresholds, changes under the influence of physiological and psychological conditions. A change in the sensitivity of the senses under the influence of a stimulus is called sensory adaptation

. There are three types of this phenomenon.

1. Adaptation as the complete disappearance of sensation

during prolonged action of the stimulus. A common fact is the distinct disappearance of olfactory sensations soon after we enter a room with an unpleasant odor. However, complete visual adaptation up to the disappearance of sensations does not occur under the influence of a constant and motionless stimulus. This is explained by compensation for the immobility of the stimulus due to the movement of the eyes themselves. Constant voluntary and involuntary movements of the receptor apparatus provide continuity and variability of sensations. Experiments in which conditions were artificially created to stabilize the image relative to the retina (the image was placed on a special suction cup and moved with the eye) showed that the visual sensation disappeared after 2–3 s.

2. Negative adaptation

- dulling of sensations under the influence of a strong stimulus. For example, when we enter a brightly lit space from a dimly lit room, at first we are blinded and are unable to discern any details around us. After some time, the sensitivity of the visual analyzer sharply decreases and we begin to see. Another variant of negative adaptation is observed when immersing the hand in cold water: in the first moments, a strong cold stimulus acts, and then the intensity of the sensations decreases.

3. Positive adaptation

– increased sensitivity under the influence of a weak stimulus. In the visual analyzer, this is a dark adaptation, when the sensitivity of the eyes increases under the influence of being in the dark. A similar form of auditory adaptation is adaptation to silence.

Adaptation has enormous biological significance: it allows one to detect weak stimuli and protect the senses from excessive irritation when exposed to strong ones.

The intensity of sensations depends not only on the strength of the stimulus and the level of adaptation of the receptor, but also on the stimuli currently affecting other sense organs. A change in the sensitivity of the analyzer under the influence of other senses is called the interaction of sensations

. It can be expressed in both increased and decreased sensitivity. The general pattern is that weak stimuli acting on one analyzer increase the sensitivity of another and, conversely, strong stimuli reduce the sensitivity of other analyzers when they interact. For example, accompanying the reading of a book with quiet, calm music, we increase the sensitivity and receptivity of the visual analyzer; Too loud music, on the contrary, helps to lower them.

Increased sensitivity as a result of the interaction of analyzers and exercises is called sensitization.

The possibilities for training the senses and improving them are very great. There are two areas that determine increased sensitivity of the senses:

1) sensitization, which spontaneously results from the need to compensate for sensory defects: blindness, deafness. For example, some people who are deaf develop vibration sensitivity so strongly that they can even listen to music;

2) sensitization caused by activity, specific requirements of the profession. For example, olfactory and gustatory sensations reach a high degree of perfection among tasters of tea, cheese, wine, tobacco, etc.

Thus, sensations develop under the influence of living conditions and the requirements of practical work activity.

6.4. Properties and types of perception

Mental processes are based on perception. Perception

- this is the reflection in the human consciousness of objects, phenomena, integral situations of the objective world with their direct impact on the senses.

In contrast to sensations, in the processes of perception (of a situation, a person), a holistic

image of an object is formed, which is called

a perceptual image

. The image of perception is not reduced to a simple sum of sensations, although it includes them in its composition.

The main properties of perception as a perceptual activity are its objectivity, integrity, structure, constancy, selectivity and meaningfulness.

Objectivity

perception is manifested in the attribution of images of perception to certain objects or phenomena of objective reality. Objectivity as a quality of perception plays an important role in the regulation of behavior. We define objects not by their appearance, but by how we use them in practice.

Integrity

perception lies in the fact that images of perception are holistic, complete, objectively formed structures.

Thanks to the structure

perception, objects and phenomena of the surrounding world appear before us in the totality of their stable connections and relationships. For example, a certain melody, played on different instruments and in different keys, is perceived by the subject as one and the same, and stands out to him as an integral structure.

Constancy

– ensures the relative constancy of the perception of the shape, size and color of an object, regardless of changes in its conditions. For example, the image of an object (including on the retina) increases when the distance to it decreases, and vice versa. However, the perceived size of the object remains unchanged.

People who constantly live in a dense forest are distinguished by the fact that they have never seen objects at a great distance. When these people were shown objects that were at a great distance from them, they perceived these objects not as distant, but as small. Similar disturbances were observed among residents of the plains when they looked down from the height of a multi-story building: all objects seemed small or toy-like to them. At the same time, high-rise builders see objects below without distortion of size.

These examples convincingly prove that constancy of perception is not an innate, but an acquired property. The actual source of constancy of perception is the active actions of the perceptual system. From the diverse and variable flow of movements of the receptor apparatus and response sensations, the subject identifies a relatively constant, invariant structure of the perceived object. Repeated perception of the same objects under different conditions ensures the stability of the perceptual image relative to these changing conditions. The constancy of perception ensures the relative stability of the surrounding world, reflecting the unity of the object and the conditions of its existence.

Selectivity

perception consists in the preferential selection of some objects over others, due to the characteristics of the subject of perception: his experience, needs, motives, etc. At any given moment, a person selects only some objects from the countless number of objects and phenomena surrounding him.

Meaningfulness

perception indicates its connection with thinking, with an understanding of the essence of objects. Despite the fact that perception arises as a result of the direct impact of an object on the senses, perceptual images always have a certain semantic meaning. To consciously perceive an object means to mentally name it, that is, to assign it to a certain category, to summarize it in words. Even when we see an unfamiliar object, we try to catch its similarity with familiar objects and classify it into a certain category.

Perception depends not only on irritation, but also on the perceiving subject himself. The dependence of perception on the content of a person’s mental life, on the characteristics of his personality is called apperception

. Perception is an active process that uses information to formulate and test hypotheses. The nature of the hypotheses is determined by the content of the individual’s past experience. The richer a person’s experience, the more knowledge he has, the brighter and richer his perception, the more he sees and hears.

The content of perception is also determined by the task set and the motives of the activity. For example, when listening to a piece of music performed by an orchestra, we perceive the music as a whole, without highlighting the sound of individual instruments. Only by setting the goal to highlight the sound of an instrument can this be done. An essential fact influencing the content of perception is the subject’s attitude, i.e., readiness to perceive something in a certain way. In addition, the process and content of perception are influenced by emotions.

Everything that has been said about the influence of personal factors on perception (past experience, motives, goals and objectives of activities, attitudes, emotional states) indicates that perception is an active process that depends not only on the properties and nature of the stimulus, but to a large extent from the characteristics of the subject of perception, i.e. the perceiving person.

Depending on which analyzer is the leading one, visual, auditory, tactile, gustatory and olfactory perception are distinguished. The perception of the surrounding world, as a rule, is complex: it is the result of the joint activity of various senses. Depending on the object of perception, the perception of space, movement and time is distinguished.

Perception of space

is an important factor in human interaction with the environment, a necessary condition for orientation in it. The perception of space includes the perception of the shape, size and relative position of objects, their relief, distance and direction in which they are located. The interaction of a person with the environment includes the human body itself, which occupies a certain place in space and has certain spatial characteristics: size, shape, three dimensions, direction of movement in space.

Determining the shape, size, location and movement of objects in space relative to each other and the simultaneous analysis of the position of one’s own body relative to surrounding objects are accomplished in the process of motor activity of the body and constitute a special higher manifestation of analytical-synthetic activity, called spatial analysis. It has been established that the basis of various forms of spatial analysis is the activity of a complex of analyzers.

Special mechanisms of spatial orientation include neural connections between the hemispheres of the brain in analytical activity: binocular vision, binaural hearing, etc. An important role in reflecting the spatial properties of objects is played by functional asymmetry, which is characteristic of paired analyzers. Functional asymmetry consists in the fact that one of the sides of the analyzer is to a certain extent leading, dominant. The relationship between the parties to the analyzer in terms of dominance is dynamic and ambiguous.

Movement

We perceive an object mainly due to the fact that, moving against some background, it causes sequential excitation of different retinal cells. If the background is uniform, our perception is limited by the speed of the object's movement: the human eye cannot actually observe the movement of a light beam at a speed less than 1/3° per second. Therefore, it is impossible to directly perceive the movement of the minute hand on a clock moving at a speed of 1/10° per second.

Even in the absence of a background, for example in a dark room, you can follow the movement of the light point. Apparently, the brain interprets eye movements as an indication of the movement of an object. However, most often there is a background and it, as a rule, is heterogeneous. Therefore, when perceiving movement, we can additionally use indicators associated with the background itself - elements in front of or behind which the observed object moves.

Time is a human construct that allows us to mark out and distribute our activities. Perception of time

– a reflection of the objective duration, speed and sequence of phenomena of reality. The sense of time is not innate; it develops through experience. The perception of time depends on external and internal factors. Just like other forms of perception, it has limitations. In actual activity, a person can reliably perceive only very short periods of time.

The assessment of the passage of time can be changed by various factors. Some physiological changes, such as an increase in body temperature, contribute to the overestimation of time, while other changes, such as a decrease in temperature, on the contrary, contribute to its underestimation. The same thing happens under the influence of motivation or interest, under the influence of various drugs. Sedatives and hallucinogens cause an underestimation of time periods, while stimulants lead to an overestimation of time.

Perception is often classified according to the degree to which consciousness is directed and focused on a particular object. In this case, we can distinguish intentional

(voluntary) and

unintentional

(involuntary) perception. Intentional perception is, at its core, observation. The success of observation largely depends on prior knowledge about the observed object. Purposeful development of observation skills is an indispensable condition for the professional training of many specialists; it also forms an important personality quality – observation.

6.5. Phenomena of perception

The phenomena of perception as factors of its organization according to certain principles were best described and analyzed by the school of Gestalt psychology. The most important of these principles is that everything that a person perceives, he perceives as a figure against a background. Figure

- this is something that is clearly and distinctly realized, has clear boundaries and is well structured.

The background

is something indistinct, amorphous and unstructured. For example, we will hear our name even in a noisy company - it usually immediately stands out as a figure in the sound background. However, the entire perceptual picture is rearranged as soon as another background element becomes significant. Then what was previously seen as a figure loses its clarity and mixes with the general background.

The founder of Gestalt psychology, M. Wertheimer, identified the factors that ensure the visual grouping of elements and the selection of a figure from the background:

1) similarity factor. A figure combines elements that are similar in shape, color, size, color, texture, etc.;

2) proximity factor. Closely spaced elements are combined into a figure;

3) the factor of “common fate”. Elements can be united by the common nature of the changes observed in them. For example, if the perceived elements are displaced or move relative to others in the same direction and at the same speed, then they are combined into a figure;

4) the “entry without remainder” factor. Several elements are easily combined into a figure when there is not a single free-standing element left;

5) “good line” factor. Of two intersecting or touching lines, the line with the least curvature becomes the figure;

6) factor of isolation. Closed figures are perceived better.

An important phenomenon of human perception can be considered its illusions. Illusions of perception

(from Latin

illudere

- to deceive) are defined as a distortion of the perception of real objects. The greatest number of them is observed in the field of vision. Visual illusions that arise when reflecting certain spatial properties of objects (lengths of segments, sizes of objects and angles, distances between objects, shapes) and movement are especially numerous. The following types can be named:

1) illusions associated with the structure of the eye. An example is illusions that are the result of the effect of irradiation of excitation in the retina and are expressed in the fact that light objects seem larger to us compared to their dark counterparts (for example, a white square on a black background seems larger than an identical black square on a light background);

2) overestimation of the length of vertical lines compared to horizontal ones when they are actually equal;

3) illusions caused by contrast. The perceived size of figures turns out to depend on the environment in which they are given. The same circle appears larger among small circles and smaller among large circles (Ebbinghaus illusion);

4) transferring the properties of the whole figure to its individual parts. We perceive a visible figure, each individual part of it, not in isolation, but always in a certain whole. In the Müller-Lyer illusion, straight lines ending in differently oriented angles appear to be unequal in length;

5) illusion of railway tracks. If you look into the distance, you get the impression that parallel rails intersect at the horizon.

The causes of visual illusions are varied and not clear enough. Some theories explain them by the action of peripheral factors (irradiation, accommodation, eye movements, etc.), others - by the influence of some central factors. Visual illusions can be caused by the influence of special observation conditions (for example, in the case of observation with one eye or with fixed axes of the eyes), optics of the eye, temporary connections formed in past experience, etc. Illusions of visual perception are widely used in painting and architecture.

Illusions can be observed not only in the field of vision, but also in other areas of perception. Thus, the illusion of gravity by A. Charpentier is well known: if you lift two objects that are identical in weight and appearance, but different in size, then the smaller one is perceived as heavier, and vice versa. In the field of touch, Aristotle’s illusion is known: if you cross your index and middle fingers and simultaneously roll a ball or pea with them, you will perceive not one ball, but two.

Visual illusions have also been found in animals.

It is on their basis that various methods of camouflage and mimicry are formed. These phenomena convince us that there are some common factors that cause illusions, and for many of them there is still no convincing interpretation. Questions for self-test

1. What are the anatomical and physiological mechanisms of sensations?

2. What is sensitivity and sensitivity thresholds?

3. What are the basic properties of sensations and perception?

4. What types of perception are there?

5. What are perceptual illusions?

Literature

Main

1. Introduction to psychology / Ed. A.V. Petrovsky. M., 1995. Ch. 4 and 5.

2. Godefroy J.

What is psychology. In 2 volumes. T. 1. M., 1992. Ch. 5.

3. Nurkova V.V., Berezanskaya N.B.

Psychology: Textbook. M., 2004. Ch. 7.

Additional

1. Solso R.L.

Cognitive psychology. M., 1996.

Table of contents

Classification, types

There are several classifications of sensations, let's consider one of them. Its author is Charles Sherrington, a British neurobiologist and physiologist of the 19th century, Nobel Prize laureate in medicine and physiology.

The scientist identified 3 classes of sensations, each of which has its own bodily zone and receptors located on it:

- exteroceptive – we receive these sensations with the help of receptors that “live” on the skin. A person feels warmth, cold, goosebumps, pressure, etc. and thus receives information about the world. If your ears are freezing outside, it means that the air temperature has dropped much below body temperature. Sherington divides this class into 2 more subclasses: contact – arise from the direct impact of an irritant on the body (you are pinched – it hurts);

- distant - are born with distant stimuli. The latter are what we see, hear, feel with our nose.

Types of sensations in this class: tactile, visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, temperature.

Physiological basis

Sensation is the source of the psychological process.

This is something that everyone has: mammals, some simple organisms, and, of course, humans.

receptors take part in their appearance . Without receptors, these experiences would not be available to humans or animals.

Receptors can be divided into two categories : those that deliver signals from the outside world, and those that analyze information coming from within. Internal information can manifest itself in feelings of pain, hunger or thirst.

Properties

The property of sensation refers to the specific information (its type) that a person receives. The totality of all properties is conditionally divided into 4 groups :

- modality – quality. Belonging to a specific sensory system (sound modality, visual, etc.);

- intensity - quantity. For example, excessively intense pain is severe pain (a lot of it);

- duration – time. Duration of a particular sensation;

- spatial localization – space. This property gives us information about the location of the stimulus.

Earlier it was said that at a specific moment in time we can experience one sensation, thus reflecting only one property of an object or object. This is normal.

However, there are special people who can feel two or more modalities at the same time. This phenomenon is called synesthesia .

For example, when listening to music, someone may experience visual sensations, certain letters or words may have their own color, taste and even smell.

Adaptation of sense organs

Prolonged contacts of stimuli and receptors are initiated by a process called adaptation of sensations. In other words, sensory organs that have adapted to regular exposure can reduce their sensitivity to the point of completely ignoring the impact. This adaptation is called negative. If, under the influence of prolonged contact with a stimulus, the intensity of sensations increases, the adaptation is called positive.

The most flexible adaptation in humans is observed to visual sensations, and the least flexible - to auditory sensations and to the experience of pain.

Sensations and perception

Sensation and perception are considered inextricably linked.

By perception we understand the mental process of obtaining information about an object through the analysis of a set of different sensations. We can say that perception is a processing process.

Example: I see something small, soft, white, rectangular in shape, light... In the process of perception, the brain actively goes through the options of images stored in memory in order to choose the one that has all the properties. A! It's a pillow! The object was recognized. Recognition does not occur if the object is not in your “database”.

Perception is not an innate ability. From birth, the child gradually learns to distinguish objects - examines, touches, tastes, smells, collecting a complete image in his head. This is a complex process that requires the active work of other mental spheres - memory, attention, thinking, motor skills, emotions.

Adronitis

0

Has it ever happened to you that after meeting a girl you felt a feeling of dissatisfaction, annoyance due to the understanding that it would take a lot of time to get to know her better (maybe weeks or months)? Or that you have no way of getting to know her at all, while she is very interesting to you. This is Hadronitis. The ancient Greeks called the male half of the house that way.

The importance of sensations

So. Sensations are divided into 3 groups, differing from each other in the location of the receptors that respond to the stimulus. This is the surface of the body, muscles | tendons | ligaments and internal organs.

From a psychological point of view, all types of sensations are important . If a person is mentally and physically healthy, he “hears” his body well, which makes life full and happy. He knows what he wants, what he likes, and what makes him uncomfortable.

As a result, such a person consciously writes the script of his existence. Therefore, she is most often satisfied with herself and her surroundings, and feels happier compared to those who are not familiar with themselves. Namely, sensations give us an idea of ourselves.

Impaired sensitivity impoverishes or distorts a person's experience.

For example, with sensory hypopathy there is a low threshold of sensations: stimuli of different intensities are perceived equally weakly. And with sensory hyperpathy (high threshold) - equally strong. These are physiological diseases.

Psychological insensitivity also occurs as a type of mental defense. This is when a person unconsciously, usually in childhood, decides not to feel.

This is how the child saves himself from negative experiences (victims of abuse, emotional rejection, etc.). As adults, such people may not feel hunger, physical or emotional pain, tolerate the disrespectful attitude of others, be completely dependent on the opinions of others, etc. Therefore, in psychology, a lot of attention is paid to sensations.

Zenozina

0

See all photos in the gallery

Zenozina is when with age it begins to seem that the years are flying by, passing faster and faster. Many people know this feeling. The name consists of two ancient Greek names - Zeno and Mnemosyne. The first was famous for his reasoning about the immobility of time, and Mnemosyne in ancient Greek mythology was the personification of memory.